San Francisco Ballet unleashed 24-year-old corps dancer Myles Thatcher’s latest creation on a wildly enthusiastic audience on February 24th – an audience that included dance world luminaries William Forsythe and Natalia Makarova, whose work was also on display in a decidedly mixed bill.

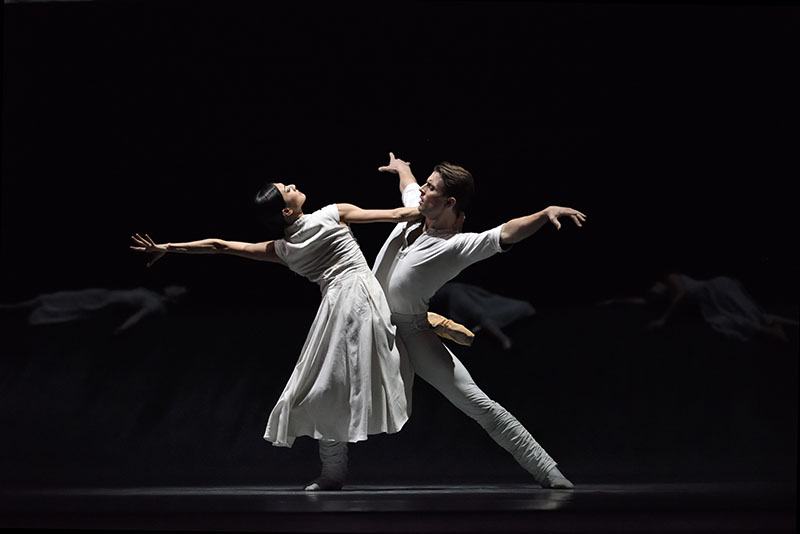

Norika Matsuyama and Stephen Morse in the world première of Myles Thatcher’s Manifesto (Photo: Erik Tomasson)

Thatcher had the cheek to venture through the knotty baroque thickets of Bach’s “A Musical Offering” and “Goldberg Variations,” well trammeled by legendary choreographers (Jerome Robbins, Paul Taylor, and Trisha Brown, for starters). What a gift his Manifesto turned to be for the 12 plucky dancers from the company’s corps and soloist ranks who danced the work superbly – led by the commanding Jennifer Stahl, partnered with great sensitivity by Sean Orza.

For all the good taste, musicality and sophistication on display in Manifesto, Thatcher will have to go through a rebellious phase if his dance-making is to break new ground. He could do worse than study the angry, furniture-tossing work of Ballet Hall of Famers Hans Van Manen and William Forsythe – though Tuesday night’s lukewarm programming showcased their less compelling creations. Two couples stalk each other in Van Manen’s Variations for Two Couples, while Forsythe’s The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude proves no more than a terrific aerobic workout for the five dancers trapped on its kooky planet.

The hardest dancing of the evening came at the end, in Makarova’s staging of the enduring “Kingdom of the Shades” scene from the 19th century La Bayadère. The scene is littered with balletic land mines, starting with the ramp down which troop 24 ghostly apparitions in tutus seemingly stitched from cumulus cloud. Nerves of steel are required, but a few wobbly legs in arabesque could not detract from the sublime spectacle.

San Francisco Ballet corps in the Kingdom of the Shades scene from Natalia Makarova’s staging of La Bayadère (Photo: Erik Tomasson)

The diamantine Wanting Zhao took our breath away in the most challenging of the three Shade solos. She came out of the starting gate all guns blazing, landing the notorious sissonnes développées and slow pirouettes with a stillness that reminds us that it is not just how high you jump or how fast you spin, but how you finish that separates the women from the girls. She bobbled an easier step moments later, but overall her austere lines and steely sang-froid left the most indelible impression of the entire evening.

– Click here to read our full review of Program 3 in the Huffington Post. –

February 26th turned out to be one of those rare evenings that offer a clear “visible sighting” of the International Space Station as it zoomed across the San Francisco sky, visible for about three minutes.

That night, ten San Francisco Ballet dancers stood motionless on stage, at the close of Jerome Robbins’ heroic Dances at a Gathering, gazing skyward in their ritual Space Station sighting, as the wistful chords of a Chopin “night piece” rained lightly down.

This plotless masterpiece, affectionately known as DAAG, opens as a Man in Brown – Joseph Walsh, whose thrilling dancing unites lyricism and bravura – relives a bittersweet memory. Watching him from the pit, magician Roy Bogas spins this memory into Chopin’s poignant Mazurka Op. 63 No. 3.

Walsh’s accomplices in the world of his memory (identified in the program only by the colour of their summery garb) drift on and offstage. They tease, seduce, fall in and out of love, spur, pester, protect, and commiserate with each other, revealing poetry in their mundane lives.

Vanessa Zahorian (Mauve) shows perhaps the greatest range of feeling, delicate in the expressive yearning of her upper body, at other times a gale-force wind. Her early duet with Carlo Di Lanno (Green) to a lilting waltz is innocent and playful; a later duet, to a heartbreaking mazurka, is stately and deliberate, leaving many things between them unsaid. Maria Kochetkova (Pink) never seems truly happy unless she’s doing something dangerous, in which she is aided and abetted by Davit Karapetyan, then by Joseph Walsh. Karapetyan dances a solo like butter, his double air turns melting into a deep knee bend. Later, he and Walsh betray a cordial rivalry in an anything-you-can-do-I-can-do-better duet. Mathilde Froustey is a zephyr in yellow; at the end of a sunny, jazz-inflected duet with the irresistible Vitor Luiz (Brick), she dives enthusiastically into his waiting arms, partway into the wings.

In a feisty dance of independence, Lorena Feijoo (Green) mocks those women-of-a-certain-age who fear loneliness. Yet later she becomes a powerful force of nature. In a charming pas de six, Di Lanno, Karapetyan and Steven Morse (Blue) toss André, Froustey and Zahorian playfully into the air.

The awesome industrial landscape of Liam Scarlett’s Hummingbird, for San Francisco Ballet (Photo: Erik Tomasson)

An inspired programming coup pairs DAAG with Liam Scarlett’s Hummingbird, another plotless ballet, new last season. Wunderkind of the Royal Ballet, Scarlett wrests unexpected emotions from Philip Glass’ relentless Piano Concerto No. 1. Co-conspirators John Macfarlane (set and costumes) and David Finn (lighting) have designed an post-apocalyptic world, the stage overhung by an enormous, curved, shimmering sail that rolls up and down to reveal more or less of a metallic quarter pipe running the full width of the stage, down which the dancers slide or roll to make their appearance.

Like DAAG, Hummingbird hints at complicated, even tragic, backstories.

Tan and Ingham appear to be trapped in a bad relationship. She may have found out something terrible about him – perhaps he is a Russian spy, or a bigamist. Frances Chung, who opens up the piece with Gennadi Nedvigin, may be the steely spymaster. The thrill-seeking Maria Kochetkova joins forces with Joan Boada to break free from the tyrannical intelligence apparatus. In the end she is propelled triumphantly through the air by the gentlemen of the ensemble, perhaps signaling the heroic destruction of the surveillance state.

Yuan Yuan Tan confronts Luke Ingham after she discovers he is a Russian spy in Hummingbird (Photo: Erik Tomasson)

In the future, when space stations whizzing overhead are no longer objects of fascination, and space travel becomes as common as riding the BART, when we encounter alien life forms in far flung galaxies who inevitably challenge us to display the superiority of humankind, let’s just throw San Francisco Ballet’s sensational Program 4 at them and be done with it.

– Click here to read our full review of Program 4 in the Huffington Post. –