1946 must have been a dreadful year for weather if John Cage’s The Seasons, which premiered the following spring, was any reflection. Merce Cunningham wrought a ballet from it. And Richard Alston, who studied with Cunningham in the 70’s, reinvented it for New York Theatre Ballet in the spring of 2018, teasing out the majesty and poignancy in the jangled score.

Giulia Faria and Joshua Andino-Nieto of New York Theatre Ballet in Merce Cunningham’s SCRAMBLE at Danspace at St. Mark’s Church (Photo: Julie Lemberger)

Alston’s The Seasons was reprised last weekend (March 14-16, 2019) at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, decades-long home to the pioneering Danspace Project, on a program that kicked off with a Cunningham jewel, titled Scramble, from 1967. Sandwiched between these formidable works was the revival of a sly tribute to Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style, choreographed by Matthew Nash in 1981.

Toshi Ichiyanagi’s score for Scramble was lost, so the piece was danced to a recording. The first sound we heard, though, as the dancers made their slow, ritual entrances was the faint but insistent peal of sirens from emergency vehicles racing down 2nd Avenue. This seemed perfectly in keeping with the soundtrack that followed, which assembled an assortment of industrial sounds into a spirited, even soothing, backdrop to Scramble’s dismantling of elements of classical ballet.

Clad in skin-tight colors out of a Crayola box, the strikingly individual dancers carved their own seemingly random paths through the sanctuary, rarely making physical contact or even eye contact, each absorbed in their own phrase-making and experiments with the quality of movement. Very precise balances on one leg gave way to generous lunges, to leaps that landed heavily and leaps that landed as if on a pillow, to revolutions in which the dancer seemed to take in the view from every direction rather than ‘spotting’ a fixed point. Occasionally a dancer would blithely grand jeté over another who was contemplating the floor in plank position, prompting the thought that this must be why the grand jeté was invented: to avoid obstacles on the ground.

Sequences in unison or canon quickly broke up and brief segments never built on each other, for Cunningham intended them to be ‘scrambled.’ That may sound dry and programmatic but it was thrilling to witness the dancers rise to the sometimes virtuosic technical challenges, and to recognize emotions that flowed from the movements themselves. At one point the women promenaded on a bent standing leg, arms cradling an invisible object, seemingly round and fragile – a birds’ nest, perhaps. With torso tilted toward the object as they revolved, they gave the impression of embracing something precious and wanting to make sure observers could see it from all angles.

The dancers’ faces betrayed little emotion, though Mónica Lima (in white) embodied a greater serenity than the others who tackled their work with slightly more ferocity. The compact,stalwart Erez Milatin (in black) exploded across the stage and at one point tried to incite rebellion among pals Sean Stewart (fuchsia) and Joshua Andino-Nieto (sky blue), pushing against their chests as they stood rooted in a lunge. But they would not yield.

The imperturbable Lima offered a benediction of sorts, fluttering a lifted leg while undulating an arm. At one moment, however, Andino-Nieto must have sensed a crack in her composure, for he was moved to envelop her in a hug.

Physical intimacy was so rare in this piece that when it happened, it was dramatic. Typically, a dancer would approach another and arrange themselves to fit into the angles made by the other – without touching – as if contemplating the possibility that their puzzle pieces might interlock. In one defiant exception, Andino-Nieto and the fiercely dramatic Giulia Faria (in sunflower yellow) slid to the ground, their bodies in full frontal contact. But it turned out they only meant to take a brief companionable nap, any hint of a liaison banished.

As the lights faded, the women bade the men farewell, placing one shin very deliberately against each man’s thigh, in turn, temporarily shifting some of her weight onto him, before casually walking off. This mysterious gesture felt like a profoundly moving ritual.

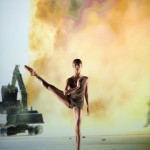

Dawn Gierling Milatin of New York Theatre Ballet in Richard Alston’s THE SEASONS at Danspace at St. Mark’s Church (Photo: Julie Lemberger)

I wrote of Alston’s Seasons at its premiere; on second viewing, it proved just as powerful. Pianist Michael Scales wrestled heroically with the John Cage score but couldn’t make me like it. As in Scramble, different qualities of movement were revealed – here, to evoke phenomena of climate. The rapid stabbing of pointe shoes into the floor in bourrées, for instance, was urgent and stuttering in Winter, then softer, wider, more generous as Summer beckoned. Big, airy pas de bourrée were slowed down to the point where we could witness the complex transfers of weight. And the descent from tiptoe or pointe often had an adventurous, windswept quality.

The irrepressible Dawn Gierling Milatin announced the advent of Spring in a solo marked by big, ebullient beats in cabriole, and whirling breezes fueled by pirouettes. Alexis Branagan and Erez Milatin floated through Summer, as carefree as the infernal score would allow. But at the outset of one impetuous lift, Branagan’s dramatic intake of breath hinted at danger to come. The crisis was full-blown by Fall, marked by a stylish and knife-edged double pas de deux for Andino-Nieto with Amanda Treiber, and Sean Stewart with Giulia Faria.

There is an economy of style to what I’ve seen of Alston’s choreography, a sense that movement and gesture have been edited out, rather than embellished – to mighty effect.

‘Omit needless words’ was one of the rules from Strunk and White’s manifesto for writers of English. Those rules were fresh in our minds from Matthew Nash’s work, which preceded The Seasons. In The Elements of Style, Nash embraced Strunk and White’s decrees on crucial matters like the placement of apostrophes and commas, and sent a trio of dancers on a series of romps as Broadway veteran Dirk Lumbard expounded on the rules in an authoritative baritone. (Though a mischievous look in his eye suggested To Hell with the rules.)

Dawn Gierling Milatin, Sean Stewart and Amanda Treiber of New York Theatre Ballet in Matthew Nash’s THE ELEMENTS OF STYLE at Danspace at St. Mark’s Church (Photo: Julie Lemberger)

A jazz score of Nash’s own invention, urbanely dashed off by Scales on piano and Ron Wasserman on bass, provided a lighthearted musical canvas. The limber Lumbard sauntered jauntily among the dancers, occasionally flirting with the two ladies while he kept the young man at bay.

Sean Stewart shone in a syncopated solo to rule #4 (‘use the active voice.’) And Amanda Treiber revealed superb comedic instincts as she slumped to the floor in fits and starts, as if driven to exhaustion by Lumbard’s delivery of one epically long and unwieldy sentence.

Such memorable moments were scarce, however, and despite its novel premise, The Elements of Style proved the least durable piece on this triple bill. The routines were often indistinguishable from those of 1950’s Broadway musicals. And the character of a suave vaudevillian who winks at the ladies, steals a kiss, and pretends to play one of them like an upright bass is unfunny in 2019.

Yet choreographers often tinker with their work – and there’s plenty of gold to mine in Strunk and White. Perhaps we’ll see The Elements of Style reimagined for a new generation.

– Carla Escoda, 22 Mar 2019