Amy Seiwert’s evening of experimental new work by herself and two other choreographers, set on her intrepid company of eight classically trained ballet dancers, is visually stunning in the intimate ODC Theatre, while the company’s stamina is severely tested by the demands on their athleticism.

The piece with the most moving premise was Val Caniparoli’s Triptych, inspired by a series of portraits of British servicemen entitled ‘We Are The Not Dead’ by photojournalist Lalage Snow, who was recently embedded in Afghanistan. Throughout the piece, the dancers mostly face the audience squarely – as opposed to the angled body facings that predominate in classical ballet – with expressions on their faces that range from blank, to tense, to quietly terrified.

Apart from the camouflage uniforms, the military ‘at ease’ stance, and partnering sequences in which the men dragged the women stiffly along the floor, there was little to mark the piece as a comment on the soldier’s lot, or on Western military intervention in the Middle East.

The music – a piece in an ecclesiastical vein by John Tavener for what sounded like electric violas, followed by a more jazzy, upbeat number by violinist Alexander Balanescu – was pleasant but underwhelming, and the choreography, particularly for the men, often tended (somewhat incongruously for the subject matter) toward smooth jazz. Movement clichés kept popping up: the high leg extension in a turned-in attitude to the side, with arms hovering like wings; explosive sissonnes en tournant with hyperextended arms slicing the air; running into a slide; and barrel turns. These steps seemed tailored to show off individual dancers’ physiques rather than advance a narrative or evoke an emotional response – hence the ultra-stretchy movements that make the most of Sarah Griffin and James Gilmer’s gloriously long limbs.

The segments in which all eight dancers executed simple movements in unison were the most riveting, and the most reflective of the inspiration behind the piece – particularly the very end when the dancers strode toward us in slow motion, with haunted faces, the sombre lighting by Jim French throwing up their enormous shadows against the back wall. Elsewhere, the fragile-looking Rachel Furst distinguished herself in a firecracker of a solo. And a sequence for Furst, Annali Rose, and Katherine Wells, models of twitchiness and quiet hysteria, was particularly fine.

Clichés of a different nature crop up in Marc Brew’s Awkward Beauty, starting with the opening upside-down lifts with the girls’ legs split in the air. Once they right themselves, the women proudly straddle the men’s bowed necks, their feet in the men’s hands like stirrups. As the men parade them ceremoniously around the stage, we are reminded of the women parading behind those stiff baroque gowns in Jiří Kylián’s wacky Petite Mort.

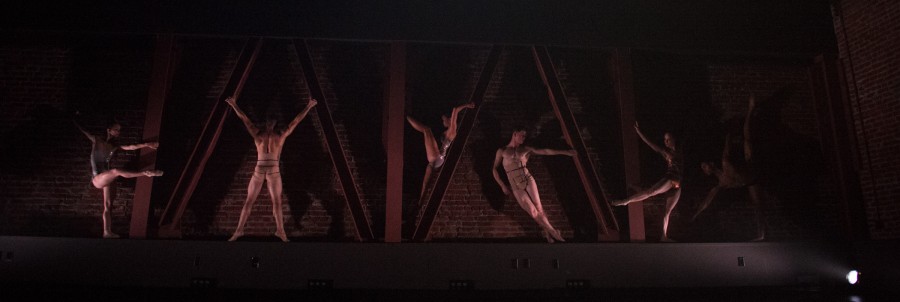

A great deal of Awkward Beauty is sheer heavy lifting, all of it in a deathly slow, continuously spiraling motion, requiring tremendous control from the women and many hours in the gym from the men. Clad by Christine Darch in shimmering futuristic leotards for the women and high-waisted briefs for the men, with bare legs and a stunning, smoky lighting design by Jim French, the overall effect is one of glamorous aliens from another planet engaged in a kind of intense alien foreplay.

The atmospheric score, tailor-made for this piece by Dan Wool, starts out with clanking noises, progresses to a pulsing techno beat, and flirts with heavy metal.

It is Brew’s solos, duets and trios that make a lasting impression, accentuating the dramatic personalities of each of the dancers. On this planet there is a definite class distinction: the women are goddesses, whereas the men are at best minor deities. The delicate Furst twists and turns and darts around the floor with an explosive power that seems to come out of nowhere. The regal Griffin elevates simple walks on quarter-pointe into high art. Furst, Griffin and Rose travel backward, stabbing the floor in bourrées of thrilling ferocity. The daredevil Wells mounts her partner, Ben Needham-Wood, as he lies face down on the floor, stepping on his back as if he were a surfboard, riding the wave as he rears up slowly. In the final moments of the piece, she lures him into a final overhead lift that mutates into a stunning spin at breakneck speed.

Seiwert’s The Devil Ties My Tongue brought us back from Afghanistan and outer space, to ordinary men and women tormented by inner demons, desperately trying to make meaningful romantic connections.

The program notes inform us that Seiwert responded literally to the text and cadences of a poem by Leonard Cohen, that starts off with: “Take a long time with your anger, sleepy head/ Don’t waste it in riots/ Don’t tangle it with ideas/ The Devil won’t let me speak.” The process is not entirely transparent at first viewing, apart from a few obvious gestures, but the piece is sufficiently thrilling without any explanation of how it was created. The dancers enter with fingers to lips, exhorting each other to silence, and proceed to engage in a series of harrowing pas de deux and a trio.

Seiwert’s strength is in her partnering work: masterful explorations of balance, weight shifts during promenades, turns and lifts that add a whole new level of difficulty to the support requirements, and an eloquent yearning of the head and upper body. She avoids the terrifying acrobatics of McGregor, the tawdry passions of Bigonzetti – there is a purity, an honesty, and a deep swell of emotion that emanate from her work, transcending the dull score by Icelandic pop star Ólafur Arnalds (a current favorite composer among modern dance choreographers.) Movement phrases end in eloquent, unexpected gestures, and the simplest placement of a hand in support of a lift can be a plea, an expression of ardor, grief, or resignation.

Weston Krukow, Annali Rose and James Gilmer in Amy Seiwert’s THE DEVIL TIES MY TONGUE (Photo: David DeSilva)

Once again Rachel Furst stood out, taking huge risks in her pas de deux with Ben Needham-Wood; she doesn’t even seem to be dancing as much as speaking passionately with her body. In the striking conclusion, the music fades as Katherine Wells advances in the grip of Brandon Freeman. He is talking urgently in her ear, trying to hold her back as she strides purposefully toward the audience – is he trying to reassure her? Trap her? Incite her to evil? The lights went down as the couple continued to struggle, and the audience had to shake off a moment of terror.

All three of these pieces contain flashes of inspiration but all are in need of editing and pruning. With heroic dancers like these, the temptation must be to push them to their limits, but sometimes less is more.

This review also appeared in the Huffington Post.

I enjoyed this program, especially the war piece. Dance is losing audiences because choreographers don’t make dances about subjects that people care about today.