THE WALKING DEAD

I do not believe in the democratisation of opinion. I believe in benign authority. And if we undermine the authority of critics then we shall descend into mayhem.

– Brian Sewell, art critic

The Canadian Journalism Foundation embraced that mayhem in a recent forum dubbed: The Walking Dead: Do Traditional Arts Critics Have a Future? And now the entire line-up of arts critics at The Independent on Sunday faces the firing squad.

The barriers to entry in the world of dance criticism have gone the way of the Berlin Wall: anyone with 3G and a subscription to the San Francisco Ballet can post their deepest darkest opinions while sipping Chardonnay from a plastic cup during intermission.

No one cares if you append smiley faces.

No fact-checker takes the wind out of your sails.

No editor prevents you from writing one-sentence paragraphs.

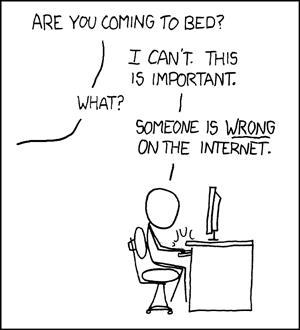

The brilliant xkcd.com regularly skewers self-appointed guardians of taste on the internet. (Credit: http://xkcd.com/)

The blogosphere is bloated with writers (Ballet To The People included) who’ve hung up their own shingles. Some of us wear two hats, self-publishing and also publishing on other platforms. Sites which publish content for free, and sites which do not pay their writers a living wage cause traditional critics to see red; to many, this threatens the traditional model of arts criticism. To others, the trend that the HuffPost started represents a new model of citizen journalism and a breath of fresh air. (The results of this survey by the International Center for Journalists reveal the urgency with which today’s purveyors of news have embraced the digital revolution.)

New York Times theatre critic Ben Brantley dismisses bloggers and Tweeters, especially those who post their “reviews” during curtain calls, saying:

I don’t think theatre is sports… I like a bit of time to digest. I don’t think you should go with your very first instinct. There should be a chance to process what you’ve seen… I don’t want to have to express my opinion in 140 characters. That’s like writing haiku. You need a certain amount of legroom to review a play properly.

Back in 2008, the brilliant food critic Jay Rayner was already asking “Is it curtains for critics?” pointing out that “consumers no longer feel the need to obtain their opinions from on high.”

Film critic Philip French told Rayner:

You don’t have to be elitist to say that not all opinion is of equal value. There is good criticism and there is bad criticism. The risk is that bad criticism will drive good criticism out of business by sheer volume.

Sean Means, film critic and optimist, insisted:

There are very few amateurs who are better than professionals. If you really are good at it you figure out some way to get paid for it. At the risk of sounding elitist, everyone has an opinion, but not everyone has an informed opinion.

The Guardian’s theatre critic Michael Billington conceded that:

Journalists of my generation have to adapt. And we have to accept that the printed word no longer has aristocratic supremacy.

Dance critics on the payroll of traditional publications find not only bloggers nipping at their heels, but also feisty, web-savvy dance artists.

In July 2012, Czech choreographer and former Artistic Director of Nederlands Dans Theater, Jiří Kylián, posted a rambling tirade on his website against “incompetent critics…who are allowed to insult people without being held responsible,” particularly certain London critics who “have tried to submerge me in their own sea of s…!”

While he didn’t name these London critics, their Commanding Officer is evidently Clement Crisp, who, true to his name, never minces words and can convey in ten what takes the rest of us several hundred. He has described Kylián’s work as “little outbreaks of aggression and dismal gropings… performed with blankest determination by three couples,” “a nasty cross-breed between tag wrestling and sessions on the therapist’s couch,” and asked “why the good Dutch do not rise up against it, as they did against the Spaniards, I cannot fathom.”

After decades of this treatment, Kylián could no longer contain himself:

They [critics] are condemned to write about whatever other people create, and this fact is probably the key factor partly responsible for the aggression and frustration which is [sic] so characteristic of some of their writing.

Artists cannot resist that cheap shot against critics who don’t actually pirouette, paint, play the piano, or declaim Shakespeare. But as Pulitzer Prize-winning music critic Martin Bernheimer famously declared:

I don’t have to be able to lay an egg to know when one is rotten.

Classical pianist Peter Donohoe concurs:

The oft-felt knee-jerk response to a bad review that the critic has no right to a negative opinion because they cannot play the music in question themselves is invalid and specious… All an educated music lover has to do is to listen regularly to a variety of performances to form a valid musical critical opinion; the rest is down to whether or not you can write coherently and whether or not you have a decent character.

WHAT IS THE POINT OF CRITICS?

Robert Johnson of Newark’s The Star-Ledger calls himself

an advocate for dance, but also a watchdog for the consumer

Phil Chan claims that:

as a critic, your most important role is not to judge, but to engage in this process and help others form their own opinions

But for you to engage and form opinions you actually have to go see the shows the critic is writing about, and a vital part of the job description of a critic is to sit through schlock so you don’t have to. After all, life is short, and tickets may cost upward of $100.

Postmodern dance pioneer Anna Halprin, whose provocative Parades and Changes, in which dancers turn the act of disrobing into ritual, met with considerable hostility when it debuted, recalled the most meaningful review she and her dancers had ever received:

It appeared in Stockholm in 1965. We did the dressing and undressing section from Parades and Changes with fear and trepidation, not knowing how our use of nudity would be received. In the States it was banned, but a critic in Stockholm referred to that section as ‘a ceremony of trust’. His giving of that name illuminated the quality of the performers’ task and gave each of them a profound image to counteract their uncertainty and fears.

Not every review is so empowering, however.

Clement Crisp firmly believes that:

Prejudice is what makes a critic interesting. Kiss ’em or kill ’em. There is no point in half-measures. People who write half-measures, like a lot of critics nowadays, are just boring. And not only boring, but lying.

Deborah Jowitt’s editors on the Village Voice apparently agreed. Only they weren’t too interested in the kisses, they wanted more knife jobs. Jowitt was forced off the Voice after 44 years of writing some of the most illuminating dance reviews in the business, apparently because she is too nice. The world is grateful that she has turned to blogging.

Peter Donohoe – who wears bad reviews like a badge of honor, including an unforgettable, sour assessment by Miles Kington of The Times (“There then followed a performance of Messiaen’s Canteyodjaya. Listening to Peter Donohoe play this piece is rather like going through a car-wash without a car”) – blithely called out the hypocrisy of the industry:

The majority of artists of any kind are inclined to completely dismiss the whole profession of critical opinion as worthless, whilst at the same time sending and posting their best reviews to anyone and everyone.

He hypothesizes that “the better educated and culturally aware the public is, the less powerful are the critics.”

New York Times dance critic Alastair Macaulay claims:

A critic who thinks about his own power and influence can be all too dangerous. I’m always relieved when I see a company director ignoring my reviews, even when I believe my points were important—as long as he or she seems to be seriously pursuing his or her own vision.

Surely Macaulay is aware of the power of his keyboard when he fires off things like:

Mr. Eifman [of the Eifman Ballet of St. Petersburg] flaunts all the worst clichés of psycho-sexo-bio-dance-drama with casual pride while he rushes headlong to commit a whole new set of artistic felonies.

and:

It’s not unusual, however, for [American Ballet Theatre] to squander large parts of the season on works that degrade ballet itself; and so again it proved this year.

Macaulay cannot deny that a damning New York Times review can dampen demand for seats at the Met.

Occasionally, a stinging blog post or tweet that goes viral will have the same effect.

Yet some sturdy artists remain unperturbed by criticism. Donohoe muses admiringly on a rival:

It certainly never did the extraordinarily brilliant Lang Lang any harm to receive a string of scathing reviews; it merely formed grist to the mill, because Lang Lang seems to be able to treat such reviews as if he is brushing off an irritating bluebottle – a level of self-confidence one can only admire. Of course, the negative reviews are more than balanced out by a plethora of rave reviews, and so the phenomenon marches on.

There is a bright side to the democratisation of dance criticism. Dance is the most ephemeral of the arts, every performance a one-off. And with the crisis in arts funding, seasons are shorter, and fewer people actually get to see a live performance. Good dance critics can capture the essential spark of the dance and keep it alive. The informality of online criticism encourages a give-and-take between critic, artists and audience, and creates an electricity often missing in traditional media.

As a practical matter, positive reviews are prized, not just because they can boost ticket sales, but also because they are essential to winning grants. So if ‘professional’ critics are being fired by the boatload, artists have no choice but to cultivate writers on non-traditional sites.

Ismene Brown argues that arts organizations must rally behind independent, professional critics. Yet dance companies are cultivating bloggers and learning to exploit social media, knowing that their ability to build new audiences depends on it.

LITTLE BETTER THAN PROSTITUTION?

Dance companies now court bloggers assiduously, sometimes running competitions on social media to drum up pre-performance hype (“Tweet a rap version of the plot of Manon and win two tickets to the ballet.”) Big-name dancers are a growing presence on social media, engaging with their fans and tooting their own horns, under the banner of taking control of their careers – in many cases, aided by powerful agents and publicists.

Dance companies and artists don’t seem to care if free publicity comes from informed critics or amateurs, as long as the message is positive and reaches a wide audience. Many bloggers do not write serious criticism at all, but operate their sites effectively as fanzines (or hate clubs), although they are often not transparent about this.

Boston theatre critic Bill Marx grouses:

The original journalistic sin is that arts coverage has rarely been held to the same exacting editorial standards as news reporting. No one would tolerate such myopic coverage of politics, but when it comes to arts coverage the line between reporting and advertising is continually being erased, rubbing out critical honesty and independence. Some of this dumbing-down has to do with good old American anti-intellectualism, the media’s banishing of the arts into the “lifestyle” cubicle, the disengagement of the arts from schools and the mass media, and ignorance of the crucial differences between publicity and cultural coverage. Because the arts are not taken seriously enough by editors to be treated as news, coverage is limited to boosterism.

The likelihood that unpaid amateurs will eventually end up in the pocket of one arts organisation or another is a compelling reason to trust only paid ‘professional’ critics. But with traditional media being snapped up by Russian oligarchs, sports team proprietors, and discount booksellers with corporate interests to protect, the impartiality of paid critics can be called into question, just as sports fans question the Boston Globe’s ability to cover the Red Sox fairly, now that one man owns both institutions. The Opera News debacle a year ago, in which the GM of the Met attempted to ban the Met’s own Opera Guild from publishing Met opera reviews, was an early canary in the coal mine of arts criticism.

For this reason, unpaid critics – most of whom have other gigs that pay the rent – can be expected to produce judgments that are freer from institutional bias. And those whose sites are not funded by advertising from the presenting organizations are even more likely to express themselves without reserve. Which is why some of the best dance writing is found in publications that aren’t exclusively devoted to dance, or are not centred around the arts.

There is sometimes a hidden agenda in the blogosphere, though. More insidious than the happy-talking P.R. sidekicks are those bloggers who don’t disclose their identities. A cowardly practice, anonymous criticism reflects badly on the critical profession as a whole.

Ballet To The People identifies herself as a teacher trained to teach American Ballet Theatre’s curriculum; further, her sister trained at the Royal Ballet, danced with ABT and Les Grands Ballets Canadiens, among other companies, and is on the artistic staff of ABT, which is reason to suspect Ballet To The People of being prejudicial toward these organizations – read her reviews and Tweets and decide for yourself whether she writes independent criticism.

She believes that the right to express an opinion that you want to be taken seriously comes with the obligation to identify yourself; anonymity should be reserved for whistleblowers who are attempting to expose massive corporate or political skullduggery, and whose personal safety may actually be in jeopardy. Recent events in the Russian ballet world aside, rarely does that situation arise in ballet.

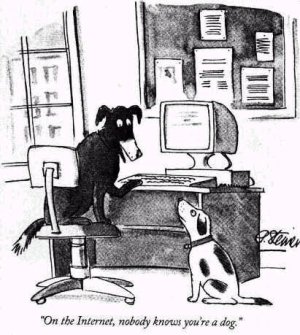

Peter Steiner perfectly captured bemusement with, and loathing for, anonymous pundits in this 1993 cartoon for the New Yorker

Anonymous ballet critics don’t really fear for their lives. But they tend to have egos the size of the Bolshoi, and longstanding personal grudges; unlike Macaulay, they are affronted when artistic directors ignore their advice. One such blogger, a connoisseur of the New York ballet world who hides behind the nom de plume of Haglund, offers the occasional trenchant insight into what she regards as the decaying standards in ballet’s equivalent of the major leagues, and her rhapsodies over individual dancers, some of whom she appears to be personal chums with, can be a joy to read. But these are eclipsed by her personal vendettas, including those against her former employer, The New York Times (for whom she worked in ad sales, and against whom she filed – and lost – a fatuous lawsuit.) These bitter resentments seep into her prose and blossom into squalid personal insults that often have nothing to do with ballet. That she feels the need to arm herself with an alias, while other critics fire their weapons unmasked, damages her credibility as a taste-maker.

For these reviewers who hold personal grudges and calcified opinions, each new review is just another opportunity to recycle the same old prejudices. The truly independent critical mind is capable of evolution, approaches every new ballet by a Eurotrash choreographer with fresh hope.

THE RIGHT TO WHINE

When asked “what is the key to developing a critical mind?” art critic Peter Schjeldahl replied “be very, very angry and be quick to blame someone.” Writing a negative review is one thing. Spewing venom is another. Most of us can tell the difference – just as U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously described his threshold test for obscenity (“I know it when I see it”) back in 1964.

Robert Johnson stoutly defends a critic’s right to whine:

In my opinion, snark is an especially appropriate gift for the High-and-mighty. It’s the pin-prick that makes over-inflated reputations shrivel and sputter. Dance is the most wonderful thing, ever, but… dances that are boring, derivative, tasteless, badly rehearsed, pretentious and/or willfully opaque do nothing to strengthen the dance community. They do not enhance its reputation, or win converts for the art form. If we say everything is good then nothing is good, depriving truly brilliant artists of the honor they deserve. Great dancers and choreographers, and not critics, set the standards; and without pruning, mediocrity will rise up to choke us.

But while the First Amendment protects your right to vilify Natalia Osipova in Swan Lake, the manner in which you do so – rather than who you write for, or whether you are paid to write – is what marks you as a professional or a boorish bush leaguer.

Few in the dance world take Jiří Kylián’s anti-Crisp rant seriously because Clement Crisp’s reviews at their most damning are never formulated as personal attacks but take-downs of what he considers displays of bad taste.

Many in the dance world, however, took umbrage with Alastair Macaulay when he made a disparaging comment about a dancer’s weight (he opined that she looked “as if she’d eaten one sugarplum too many”) and probably made Macaulay wish that his editor hadn’t been asleep at the switch the night he filed that Nutcracker review.

In 1995, New Yorker dance critic Arlene Croce ignited a firestorm with her infamous “Discussing the Undiscussable,” in which she denounced a work by Bill T. Jones – which used images and voices of terminally ill patients, and which she refused to see – calling it “victim art,” “intolerably voyeuristic” and a “baiting of the audience.”

Victim art defies criticism not only because we feel sorry for the victim but because we are cowed by art

she charged, accusing not just the artists but the arts bureaucracy, donors and the NEA for nurturing victim art at the expense of more deserving work, driven by liberal guilt and political correctness. Nearly 20 years later, critics and artists continue to toss this hot potato around each time a new work emerges that involves disabled artists, celebrates political causes, or otherwise makes a segment of the audience squeamish.

Just as Croce asked us to consider whether all art is worthy of being seen and criticized, audiences today must ask whether all criticism is worthy of being read, whether what passes for criticism is truly informed and dispassionate.

A literate, engaging review makes readers wish they had sat next to the critic at the theatre. A spiteful, contemptuous screed on the other hand reflects a mind obsessed with old grudges and bent on revenge. Peter Schjeldahl may have been only half-joking when he suggested that critics are fundamentally angry people, but he operates in a world where the angry people have editors ready to dispense metaphoric Valium, laxatives, and nicotine patches. It is not the independent bloggers who represent the last bastion of objectivity and civility in the scrappy digital age; rather, it is the editors who are free from advertising revenue pressures. Alas, they’re a dying breed, as more publications are snapped up by large corporate interests.

Better late than never: stung by recent online threats of rape and murder against women, Arianna Huffington declares that anonymous commenters will shortly be banished from the Huffington Post: http://www.thedrum.com/news/2013/08/22/huffington-post-ban-anonymous-comments-no-more-hiding-says-arianna

Arianna Huffington is a smart businesswoman. Whether she has deep principles is unknowable. The kind of attacks that have been made on-line suggest that the perpetrators are so unbalanced they might physically harm their targets. In which case the Huffington Post could be liable for negligence or worse by providing a platform for these crazies to stoke their hatred. She’s being prudent. Don’t be so quick to put a halo on her head though.

If you don’t approve of anonymous writers then why do you promote anonymous bloggers on your blog roll?

Maybe they aren’t always polite and maybe they make spelling and grammar mistakes but that is what free speech in America is about, being able to say whatever you think without censorship. Once you start requiring good manners and clean speech you are practicing censorship.

There’s a difference between anonymous bloggers and anonymous critics. I’m a big fan of a few bloggers who keep their identity a secret, whose writing has an appeal that comes partly from the mysterious persona that they cultivate. I don’t care who they are, have no interest in finding out – in fact, I think a little bit of their magic might die if they did “out” themselves.

But they don’t write criticism – or if they do, it’s the occasional off-the-cuff review that is part of the larger “fiction” they’re creating.

If you make a habit of critiquing professional performances, however, you have to establish yourself as a professional too. Impossible to do that without identifying yourself. It’s an insult to the artists to have you pick apart their performance while hiding behind a mask.

I am on less secure ground when it comes to the “this is what America is all about” thing. My instinct tells me that censorship happens when ideas are squelched, not when language is scrubbed.

Maybe some critics are more bitter than others but so what? It would be boring to read reviews that are all equally civilized and full of sweetness and light. Variety of opinions and variety of tones are what make review surfing interesting. Anyway Haglund is speaking from his personal experience which is different from yours and different from the New York Times critic. Readers are interested in authentic voices. We don’t need to know who is behind the voice.

I think it’s a problem when personal hatred and a desire for revenge so obviously take over one’s criticism.

Hate-filled speech undermines one’s credibility, especially when trying to persuade readers that your point of view is the superior one.

Before blogging critiquing was a one way conversation, now it’s become a vibrant healthy argument. Anyone can participate which is what Ballet to the People of all people should want. Like any argument these can get heated and out of control, but that’s because people have strong opinions and ideals. You have to be tough to stay in the fight, and many old style reviewers don’t have the guts for brawling, they’d rather have a bunch of timid readers sit quietly through their lectures.

And btw hating on someone online is not ok if that person you’re hating on is smaller or weaker than you. Read Haglund: he is hating on powerful institutions like ABT and New York City Ballet and big-name dancers who have lots of money to promote themselves. He supports the underdogs, the dancers who are not getting the breaks they deserve. That’s not civilized???

Survival of the fittest. If you can’t take the heat stay out of the kitchen. Blogosphere creates level playing field for people with strong opinions. But true that the loudest, dirtiest mouths often get the most attention and it’s not always deserved. Still, when you come across a bully you have two choices – stand up to them/call them out on their shit or avoid them/ freeze them out. Nothing shuts a bully up as effectively as being ignored.

Not to point out the lack of quality control on this site but am I the only one noticing the careless use of pronouns in this thread? First Haglund is a she then she’s a he… which is it people?

Since Haglund is anonymous, the gender may be unknown–therefore shifting between one and the other may make sense.

Well I had the good fortune of sitting next to her and her entourage at the Met.

Oh good Lord just more proof that anonymity on the internet brings out the creeps, the paranoids, the boorish and the nitwits – what should have been a reasonable and enlightened debate on the issue of invasion of privacy has spiraled down into this mess: http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2014/04/people-dont-like-google-glass-because-it-makes-them-seem-weak/360919/#comment-1350601751 (note that the few reasonable voices belong mainly to people who are using their real names, or handles that can easily be traced back to real individuals)