The Butterfly Lovers – one of those hybrid East-meets-West story ballets meant to showcase Chinese command of classical Western technique while celebrating a traditional Chinese theme – blew into Berkeley on a cloud of garishly colored butterfly tutus, courtesy of Shanghai Ballet at Cal Performances. This conventional tale of star-crossed lovers, with a cross-dressing twist, contains some spectacular and moving moments amid stretches of tedious, unremarkable choreography.

The curiously static first and second acts, set in the grounds of an ancient Chinese academy, are enlivened by the bold and brisk dancing of the male corps and by the splendid attack of Zhang Yao in the role of the arrogant and cunning Ma Wencai, a schoolyard bully.

Our spunky heroine, Li Chenchen in the role of Zhu Yingtai, prohibited from acquiring an education due to her sex, has disguised herself as boy to gain entrance into this bastion for the superior sex. She develops an attraction to fellow student Liang Shanbo, danced by the courtly Wu Husheng, who relishes her company unaware of her deception. Contemporary Western choreographers would be tempted to explore the homoerotic potential in this situation but choreographer and artistic director Xin Lilli plays it safe.

The stilted and restrained choreography through much of the first two acts gets no help from the florid score, which seemed to be stuck in a melodramatic gear. Though intriguingly orchestrated for Chinese and Western instruments, the score, with its unflagging 2/4 or 4/4 time signature, does not build any tension but hangs over the ballet like a heavy fog. (Ballet scores traditionally change up time signatures and dynamics, and make generous use of 3/4 or waltz time, which helps the dancers stretch their lines and achieve the desired buoyancy when jumping.)

Striking dance sequences include a “dream” pas de deux, original and contemporary in feel, and movingly executed by Zhou Haibo and Zhang Wenjun, and an arresting fan dance for the male corps, which required the men to wield enormous wooden fans while executing a challenging sequence of jumps. The Chinese ballet companies cultivate a uniform look among their dancers that – with the exception of Paris Opera Ballet, the Bolshoi and the Mariinsky – is no longer the standard for world-class companies, which increasingly prize individuality. The dancers of Shanghai Ballet are on the tall side, with willowy physiques and clean technique – even in the flashier, more acrobatic interludes that recall their Soviet heritage – and this ballet showed off the men particularly well.

Among the women, Tie Jiaxin stole the second act on Saturday night with her supremely elegant and lyrical Butterfly Queen, her lines and gracious upper body carriage a match for any of the reigning Russian ballerinas. This act was otherwise marred by the lurid neon green of the corps women’s butterfly tutus.

The ballet takes off in the third act, when Zhu returns home to her wealthy parents who insist on marrying her off to the wicked and well-connected Ma. The opulence of her family home, in a striking deep red and gold design set against the backdrop of a magnificent tree in autumn splendor, recalls the stunning blood red Act III set design for John Cranko’s Onegin (a story ballet that has proved immensely popular in China). The stately ensemble dance that opens this act, with the company costumed in fabulous red, gold and orange robes and headdresses, rivals the famous ballroom scene in Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet. The robes’ voluminous sleeves and panels billow dramatically as the dancers pivot and turn, conveying the sense of power that comes with wealth.

Against this grandeur, Li, in a pale pink dress, performs an achingly beautiful solo full of quick changes in body facing, with crystal clear articulation of the feet and a melting upper body. No longer hampered by her male disguise, she relaxes into a soft and alluring, but defiant, femininity. We are drawn in particular to the expressiveness of her hands, which ripple in distinctly unclassical but very lovely movements.

Zhang makes a brash entrance and, as Zhu’s father forces her to dance with him, the music finally soars. Li’s exquisite bourrées as she attempts to elude Zhang speak volumes, and after her father and Zhang storm off stage, her torment is palpable in her face, in her deep forced arch on pointe, and in the desperation of her soaring grands jetés.

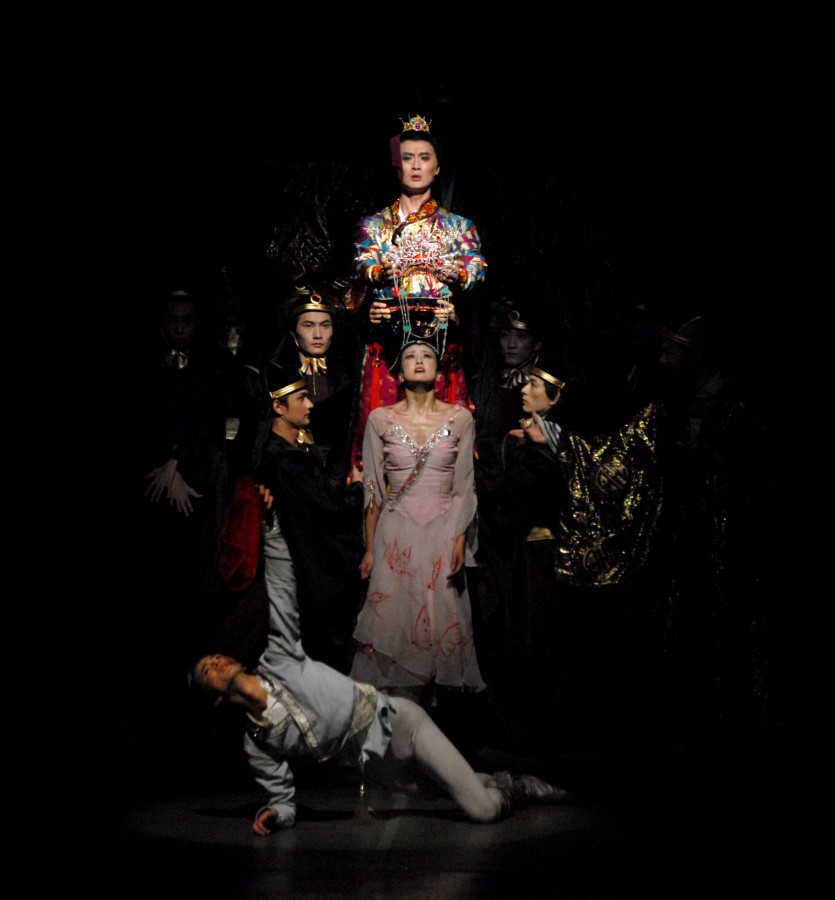

The ballet hits a climax when Wu shows up to declare his undying devotion and Zhang returns to beat his rival to a pulp. Like most bullies, he is a coward and calls in the triads to do his dirty work. The score is tremendous here, ominous and percussive, as the Chinese mafiosi, in dark capes, advance slowly toward the audience and the hapless Wu with leaden stomps. We are engulfed in terror as the gang tramples Wu to death with every Russian jump in the ballet vocabulary.

Act IV opens to a chilling winter at Liang’s grave. The butterfly corps women now flaunt pale blue and silvery tutus and their variations, delicate and haunting, reflect and amplify our heroine’s sorrow. The score turns rhapsodic, and Ballet to the People no longer cares if she never hears a 3/4 time signature again. The women carve the air with their arms in sorrowful, sweeping arcs that contrast with their clean and restrained pointework. At one point, in a delightful bow to George Balanchine, they advance in single file toward the audience with darting legs, swiveling hips and startling, elegant flourishes of the arms.

The ensuing winter storm and the transformation of the lead couple into silvery white butterflies appear somewhat cheesy and unnecessary after the glories of the previous scene; the re-emergence of the butterfly corps in gaudy tutus was another artistic howler. We would have gone home entirely happy had the curtain come down on a heartbroken Zhu mourning at her lover’s grave, surrounded and protected by her icy neoclassical butterflies.

– This review also appeared in the Huffington Post. –