The Joffrey Ballet’s ambitious mixed bill, Stories in Motion, exploded onstage at the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago on September 20th: three ballets that trace a timeline of the infiltration of Modernism in ballet – from George Balanchine’s final work for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1929, to Antony Tudor’s 1936 distillation of sexual mores in Edwardian England, and Yuri Possokhov’s high-tech riff on rape and arson set against the backdrop of an ancient Japanese warrior culture.

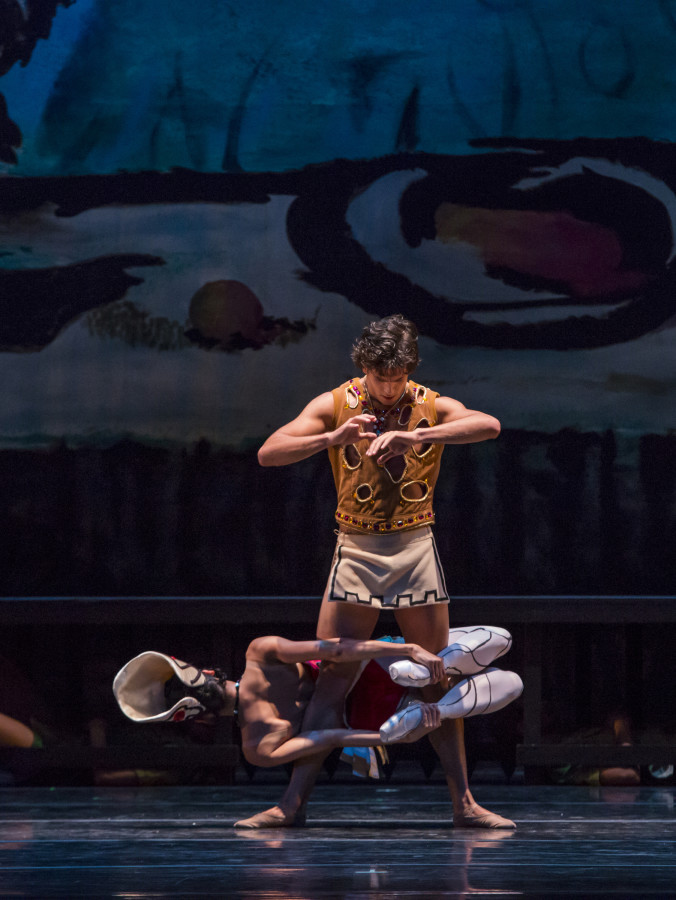

With the ink barely dry on the Surrealist Manifesto, Balanchine recounted the biblical allegory of the Prodigal Son against vivid, Fauvist backdrops and introduced a Greek chorus of comic thugs, very effectively and menacingly danced by the male corps. The strapping Alberto Velazquez tore up the stage in the title role on Saturday night, utterly convincing as the youthful rebel who succumbs to a Siren, then returns home a wretched mendicant. The supremely athletic Christine Rocas was most bewitching when wrapped around Velazquez: locking him inside her leg lifted in attitude devant, and later slithering provocatively down his body in a backbend while gripping her ankles. But Rocas never ventured into the territory of the strange and sinister, as other great interpreters of the role have done; she appeared about as sinister as an NFL cheerleader. And a slight slip of technique was visible as she repeatedly sacrificed turnout at the hip in search of higher leg extensions to the side.

While the final scene of the ballet contains no formal dance movements whatsoever (unusual for Balanchine), anyone who ever had a father could not fail to be intensely moved at the sight of Velazquez hoisting his limp and broken body into his Father’s arms. Whereupon the Father – portrayed with great dignity and reserve by Artistic Director Ashley Wheater – wrapped his cloak around his son’s near-naked body and carried him solemnly toward the house.

Victoria Jaiani as Caroline & Dylan Gutierrez as Her Lover in Tudor’s Lilac Garden (Photo: Cheryl Mann)

Tissues emerged to dab at eyes during intermission, and were redeployed once the curtain rose on Tudor’s Lilac Garden, as hay fever threatened. The stage was cloaked in dark, sheer drops painted with abstractions of flowering bushes so thick that we sensed the oppressive perfume of lilacs. We have gatecrashed a garden party of well-bred folk of the Downton Abbey era (Season One) during which the aristocratic Caroline and The Man She Must Marry (presumably a wealthy man chosen to buttress her family’s dwindling fortune) have several anguished, clandestine encounters: she with Her Lover and he with An Episode in His Past. These interludes keep getting interrupted, however, by nosy party guests who drag the two couples back to the formalities of social dance.

April Daly as An Episode in His Past & Miguel Angel Blanco as The Man She Must Marry in Tudor’s Lilac Garden (Photo: Cheryl Mann)

Tudor employed a minimal range of classical ballet movement for the legs, with precise and delicate footwork – one impassioned duet consists merely of a series of sissonne jumps that change directions – but he defied classical tradition in his use of the arms, which are expressive in a naturalistic manner. His default position of the arms is very low, almost pinned to the side of the body in a stance that conveys vulnerability – in contrast to the generous, open and rounded classical carriage of the arms. The heights of sexual fervor are expressed twice in Lilac Garden, when each of the two male leads – very finely danced by Miguel Angel Blanco and Dylan Gutierrez on Saturday night – upends his partner, her pointes momentarily shooting skyward.

Dylan Gutierrez, Victoria Jaiani, Miguel Angel Blanco, April Daly in Tudor’s Lilac Garden (Photo: Cheryl Mann)

Tudor dancers do not emote; through their steps, through changes in body tension, through gesture and touch they reveal desire, pain and conflict to the audience even as they seek to conceal those emotions from one another. The Joffrey gives the most exquisite performance of this understated, interior masterpiece that Ballet to the People has ever witnessed, with a fine interpretation of Ernest Chausson’s Poème delivered by the Chicago Philharmonic and solo violinist David Perry. Victoria Jaiani is transcendent as Caroline, while the lovely and musical April Daly strikes a contrast as her spunky rival.

Fabrice Calmels as the Samurai & Victoria Jaiani as the Princess in Possokhov’s RAkU (Photo: Cheryl Mann)

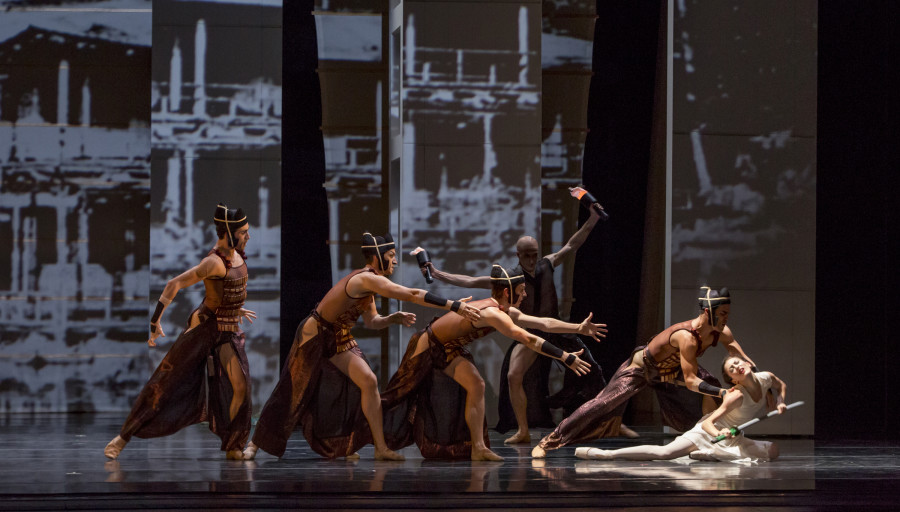

Leaping forward into the internet age – signaled by stunning video projections and the anarchic use of upper- and lower-case in the ballet’s title – RAkU plays fast and loose with the story of the 1950 burning of Kyoto’s Temple of the Golden Pavilion by a mentally unhinged monk. Not unlike the preceding pieces, this is highly stylized costume drama, though primitive and erotically charged in a different way. The cinematic score by Shinji Eshima, like the choreography, has moments of restrained, hypnotic beauty, and of oneness with nature (cue the sound of crickets). Then all hell breaks loose: kimonos are whipped off bodies by invisible wires; a quartet of stomping samurai slash the air with swords; their leader, the commanding Fabrice Calmels, troops off to fight in distant lands, leaving his princess bride – once again, the luminous Victoria Jaiani, this time in heroic mode – to be stalked and raped by a mad monk (Temur Suluashvili, in a heartstopping performance) who then torches the temple.

The gang of four return, this time with a casket bearing the ashes of the princess’ husband, and proceed to rape her, too. (An unforeseen plot twist: weren’t these warriors loyal to her husband barely five minutes ago? But this narrative defies logic, as do the librettos of many classic ballets.) In her grief and torment, the princess flings her husband’s ashes over her body and toys with suicide, wielding her husband’s sword. It’s a wonder she doesn’t expire, but the Philharmonic keeps playing, Buddhist monks start chanting, snow starts falling, and the princess-who-won’t-die signals her descent into madness by repeatedly raising a sickled foot (in ballet terms, the ultimate sign that Modernism has triumphed) then either falls asleep or dies (unclear).

Possokhov’s inventiveness flags as he repeats phrases – notably the cruel flinging of the princess’ broken body into the air during the gang rape. And there was not much choreographic distinction between the intimate bedroom pas de deux of the princess and her husband and the first rape scene. Possokhov’s treatment of sexual violence was more original and compelling in his 2013 Rite of Spring for San Francisco Ballet.

The visual splendor of RAkU is undeniable, however, anchored by the breathtaking scenery and projection design by Alexander Nichols and mouthwatering costume designs by Mark Zappone. The references to a more or less imaginary ancient Japanese warrior culture follow longstanding ballet tradition that imagines an India full of Hindu temple dancers who bare their midriffs in bikini tops (La Bayadère), and a Russia under siege by monstrous Oriental despots (Firebird). The hunky samurai of RAkU fight in long flowing silk skirts slit alluringly on the side of the hip, revealing vast swathes of vulnerable anatomy. The demented monk frequently assumes the plank position and other yoga poses, but also soars thrillingly in strings of double saut de basques that remind us that not only is this ballet, it is RUSSIAN ballet. Political correctness aside, this is entertainment of a very high order, which the artists of the Joffrey deliver impeccably.

– This review originally appeared in the Huffington Post. –