Fine art works should be like sunshine from the blue sky and the breeze in spring that will inspire minds, warm hearts, cultivate taste and clean up undesirable work styles.

– Chinese president Xi Jinping, speaking at the October 2014 Beijing Forum on Literature and Art

There will always be the need for specialized facilities for the desperados, the irredeemable, and the ruthless, but Alcatraz and all that it had come to mean now belong, we may hope, to history.

– Director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons, James Bennett, on the closing of the federal penitentiary at Alcatraz in 1963

Any artist who is not an activist is a dead artist.

– Ai Weiwei

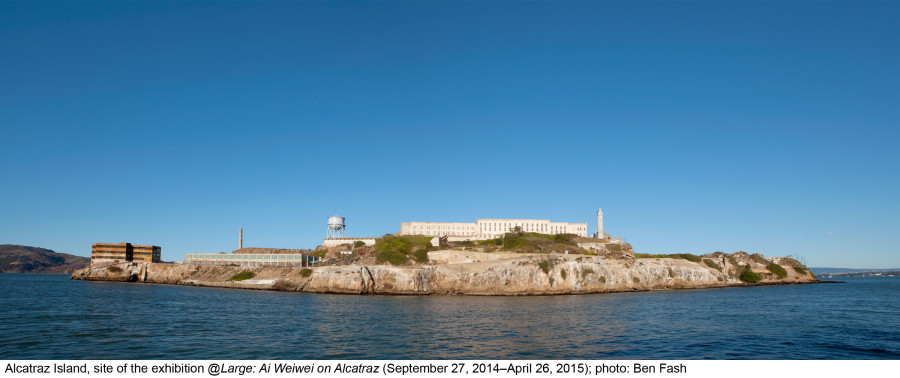

24 hours after the terrorist slaughter at the offices of French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo, daytrippers sailed to Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay on a picture postcard day to be met with another ominous reminder of how fragile is our freedom of expression. Seven installations by Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei sprout amid the rusting steel bars, broken windows and peeling paint of a cellblock, a dining hall, hospital ward, and a forced labor facility (euphemistically labeled the New Industries Building when it was built in 1939).

A thorn in the side of the Chinese government, Ai has been stripped of his passport and is no longer free to travel. Government censors are perennially trying to stamp out his prankish, irreverent presence on social media as well as his more sober internet campaigns, such as the organizing of volunteers to compile and publish the names of the more than 5,000 schoolchildren who died in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, buried alive under the rubble of shoddily built public schools.

As C. Wright Mills argued, “those without power need to connect personal troubles with public issues,” and Ai has taken it on himself to create those connections at great risk to himself. Thus he continues to create and exhibit work, much of it site specific, in elaborate cross-continent collaborations with curators and craftspeople, sometimes armies of them, from Taipei to Tokyo, Brooklyn, Berlin, and Blenheim Palace.

One would have to be in a coma to miss the great irony of this latest exhibit at Alcatraz – the site of the transformation of a Civil War-era fortress into a military prison, then an infamous federal penitentiary, and now a sanctuary for nesting birds – by an art world superstar who rails vociferously against violators of human rights while he himself is effectively incarcerated.

Ai Weiwei readily acknowledges that his celebrity is in no small measure due to the oppressive tactics of the Chinese government.

“Righteousness”: Umbrella Movement logo competition entry. Artwork by Chun Man, courtesy Kacey Wong.

If a wedge is to come between this irresistible force and immovable object, it may well be the handiwork of the artists of Hong Kong’s nascent Umbrella Movement. This civil disobedience campaign is aimed at holding China’s feet to the fire on the promise made at the time of the 1997 handover from British rule, to allow Hong Kong to move toward a full democracy on its own terms. It was born out of a campaign known as Occupy Central With Peace and Love, in which groups led mainly by students sought to take over several key thoroughfares in the bustling city. The yellow umbrella became the accidental symbol of the Occupy movement, after protestors started wielding umbrellas to protect themselves not only from rain, but also from pepper spray and tear gas fired by the police.

Professor Kacey Wong of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University School of Design was one of several who orchestrated outbursts of street art to inspire the protesters. A “logo competition” for the movement, which attracted hundreds of entries, is now catalogued on his Facebook page. A conversation with him highlights the sharp divide between artists in Hong Kong and China, the former having grown up in a much freer world than the latter. Though they may share bloodlines, language, and a desire for democracy, travel restrictions and mistrust often isolate Chinese artists from their Hong Kong brethren. “The danger of ‘being disappeared’” as Wong puts it, is a very real threat that keeps him and other Hong Kong artists out of China.

Few artists in China today defy the authorities as brazenly as Ai Weiwei, though the work of many – like He Yungchang, Yue Minjun, Liang Shaoji, Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Xing Danwen, Cao Fei, Zhang Xiaogang and Guo Jian – contains both overt and coded criticism of the government, with content sometimes grim and unnerving. (He Yunchang’s methodical burning of every stitch of clothing on his back, and his slicing into his naked body to remove one of his own ribs, pushes the already far-flung boundaries of performance art.)

But Hong Kong still marches to a different drummer, and the fate of its protest art may be as much a beacon of China’s future as Ai Weiwei’s struggle with his oppressors.

– For our full review of Ai Weiwei’s exhibit on Alcatraz, and more glimpses of the art of protest in Hong Kong, sail on over to the Huffington Post. –

– Ai Weiwei @Large, sponsored by the FOR-SITE Foundation, continues through April 26th, 2015 at Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay. –