Many ballet-lovers subscribe to the myth that George Balanchine’s 1954 reinvention of the Russian classic for New York City Ballet “sparked an American holiday tradition” – in the words of Laura Jacobs, who penned a fascinating exploration of Balanchine’s Nutcracker for Vanity Fair, even as she played fast and loose with the essential detail of the ballet’s arrival on American shores.

Jennifer Fisher, in Nutcracker Nation, her sociological meditation on the industry that props up practically every American ballet company, identifies Willam Christensen’s 1944 production for San Francisco Ballet as the first full-length American production, whose enormous popularity astonished even its creator.

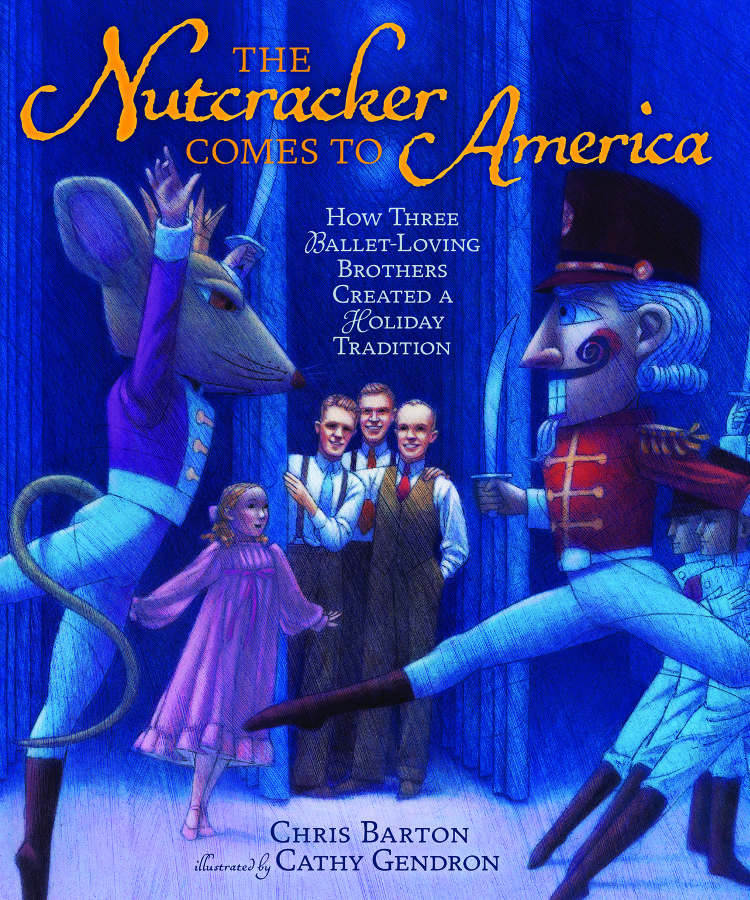

And now a captivating children’s book arrives to set the record straight for the younger generation.

In The Nutcracker Comes to America, author Chris Barton introduces us to the remarkable Christensen brothers, Willam, Harold and Lew, whose “dance-loving, violin-playing grandfather” emigrated from Denmark and settled in Utah. We follow the young men’s zigzagging journeys from the ballet studio to vaudeville stages across the country, to New York to dance for the greats like Balanchine and Fokine, and into the army, against the backdrop of World War II.

The restless Christensens couldn’t seem to stay put. Which turned out to be providential for American ballet, especially on the West Coast. Willam brought ballet to Portland, Oregon, and later established the formidable Salt Lake City company that would be known as Ballet West. In between, there was San Francisco, where he and Harold spun off the ballet troupe from the opera company, while Lew “traded in his ballet shoes for army boots.”

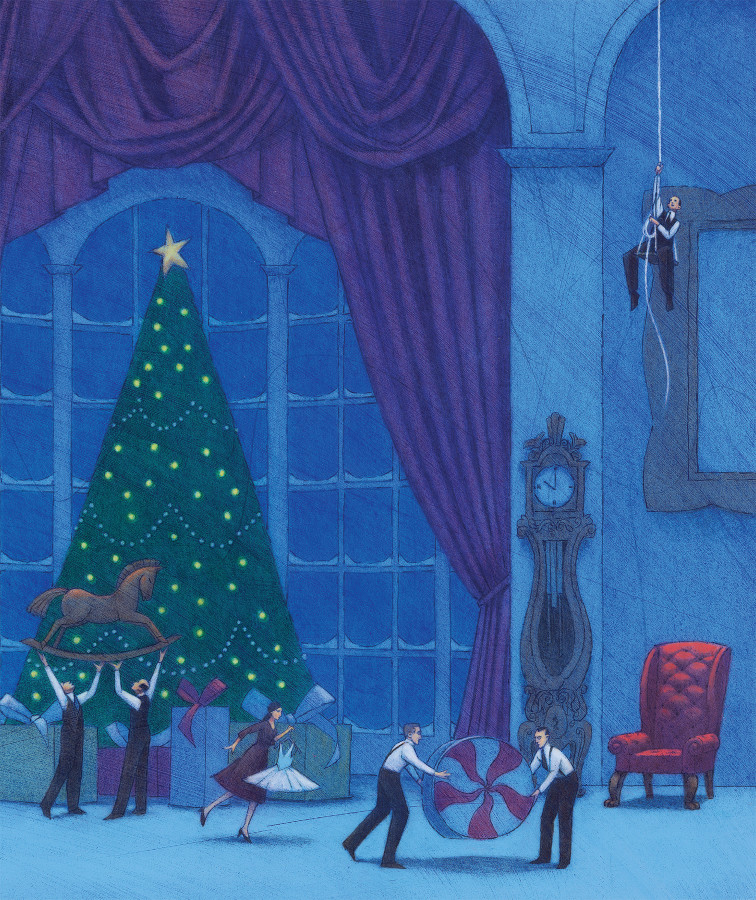

It was during wartime America, when many dancers were off fighting and money was especially scarce, that Willam needed a big hit “to keep ballet alive in San Francisco.” He loved the great Russian classics and, though he’d never seen them performed – at least not in their entirety – he would research them painstakingly. For The Nutcracker, he cornered Balanchine and Alexandra Danilova, as the two Russians had danced in Petipa’s version in St. Petersburg. He had them recount for him as much of the choreography as they could recall.

The Christensens’ peregrinations, and the delightful goings-on onstage and backstage during the first Nutcracker, are illuminated in the arresting illustrations of Cathy Gendron – multiple coatings of thin oil glaze meticulously layered over pencil drawings on gesso, then lightly textured, as if burnished by steel wool. The colors glow softly on the page, and the whimsical yet realistic figures convey energy and emotion that will intrigue adults as much as children.

Don’t be misled by the book title. This is much more than the story of the transplanting of a famous Russian ballet. And not just a book for little girls who dream of dancing in tutus and pink satin pointe shoes. This is a real-life adventure story about “a trio of small-town Utah boys” with grit and talent, who bucked stereotypes, endured failures and persevered, and who individually and together enriched the cultural life of America.

Throughout the children’s tale and the more grown-up addendum, a light wit prevails, and there is much to read between the lines. About the 1892 premiere of The Nutcracker at the Mariinsky Theatre, Barton comments laconically, “It does not catch on.” And those who are familiar with the hard business of ballet likely know that it was the Christensens’ sheer determination that kept San Francisco Ballet afloat for decades.

Many young dancers in training are unaware of the colorful history behind the Nutcracker. Barton and Gendron’s new book does its bit to fill that gap, with charm and wisdom.

– Excerpted from our book review that appeared in the Huffington Post in July. –