With just a few days to make the most of Indian summer in New York City, Ballet to the People was tempted to spend every sunshiny day sizing up the buskers in Central Park, remodeling Olafur Eliasson’s white Lego installation on the High Line, and cheering on the Mets as they battled the Dodgers at Citi Field.

But the sizzling heat in the museums and theatres was too tempting.

Thomas Hart Benton, City Activities with Dance Hall, from America Today (detail), 1930–31, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

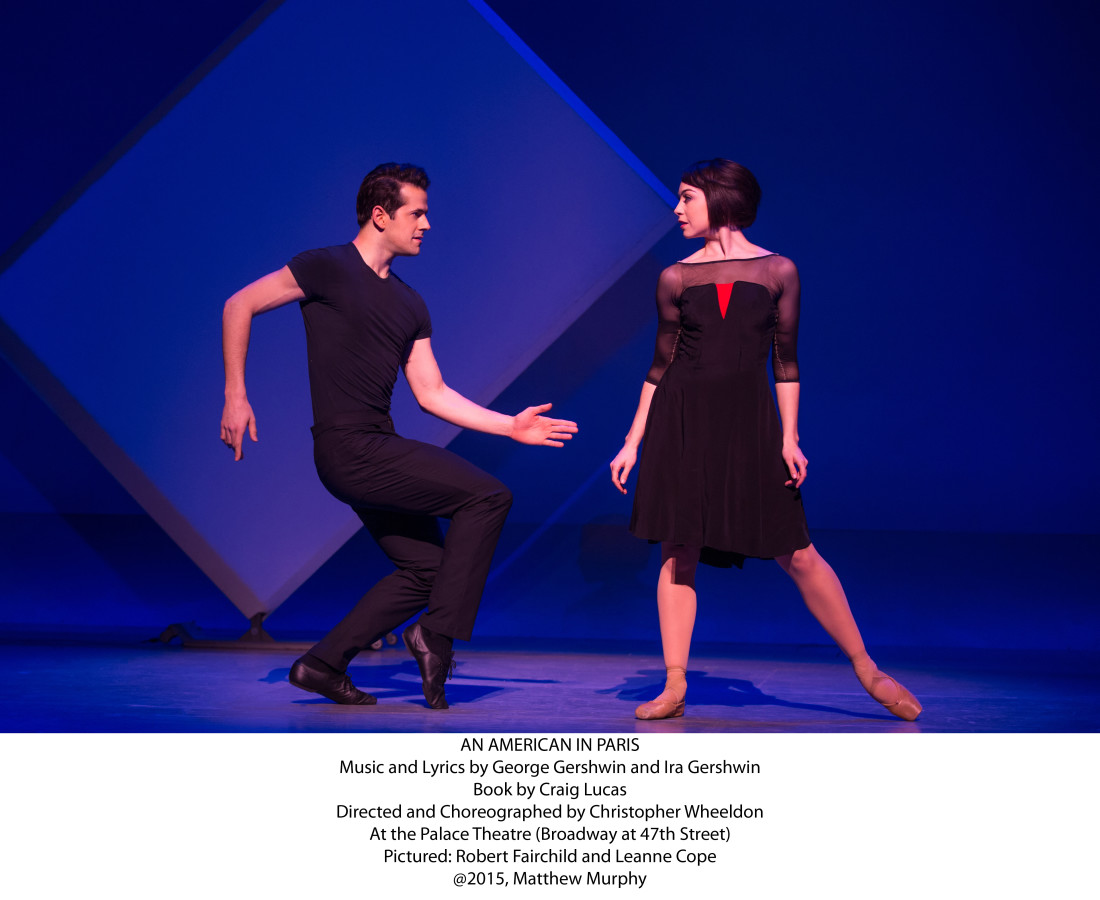

An American in Paris (Palace Theatre)

Christopher Wheeldon’s elegant reimagining of this Gene Kelly masterpiece lost none of its poignant magic on second viewing, five months after the first (click here to read our review in Bachtrack). Playwright Craig Lucas’ chiaroscuro rendering of the original screenplay is buoyed by Rob Fisher’s delightful plundering of the Gershwin songbook.

Leanne Cope in the role of Lise, the ingénue-with-a-secret, gazed as if for the first time into Robert Fairchild’s eyes, startled at her sudden feelings for this handsome American soldier. The tension between new pals Fairchild, Brandon Uranowitz (cynical American composer, wounded in the war), and Max Von Essen (French song-and-dance-man-with-more-than-one-secret) in post-Liberation Paris felt as crisp as the military uniforms still seen on the city’s streets.

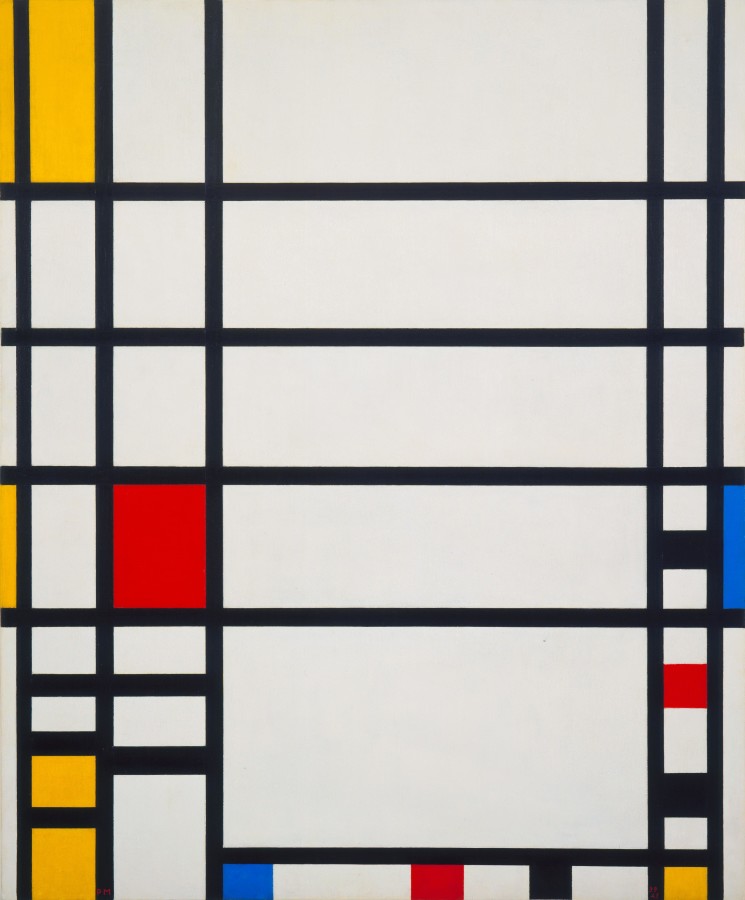

The chic set designs make judicious use of high tech effects, perfectly showcasing Wheeldon’s sophisticated choreography. This culminates in a whiz-bang ballet inspired by the canvases of Mondrian, fresh in our memory from our afternoon pilgrimage to MOMA.

Daddy Long Legs (Davenport Theatre)

Paul Alexander Nolan (Jervis Pendleton) and Megan McGinnis (Jerusha Abbott) in DADDY LONG LEGS at the Davenport Theatre

Magic on a smaller scale was being made at the Davenport Theatre (a cozy space off Broadway in a repurposed fire station) by the entrancing musical adaptation of the 1912 novel by Jean Webster. Many an empty childhood can be traced to a lack of acquaintance with this absorbing tale, told in the form of letters between a feisty orphan and the shadowy philanthropist who pays for her college education. Lifting passages from these letters, adaptor-director John Caird and composer-lyricist Paul Gordon have fashioned a lively, unsentimental two-character operetta, energized by the talents of Megan McGinnis as Jerusha Abbott (whose modest ambitions are to “bake lemon pies, cure disease, and win the Nobel Prize / like other girls”) and Paul Alexander Nolan as the aristocratic renegade Jervis Pendleton.

With two characters on a postage stamp-sized stage, Caird manages to build as much suspense as top-drawer Hitchcock. We delight in Jerusha’s budding feminism and socialism – she strives to be a Fabian, one of those “socialists who are willing to wait,” believing social change should be gradual (so people will survive the shock.) And we are troubled by the web of lies spun by the remote, insecure Jervis: “happy in my hypocrisy / pretending I’m the man I’ll never be,” he believes that “charity builds a wall of gratitude / that can never be climbed.” Yet he falls perilously in love with her.

Caird and Gordon stay faithful to Webster – even though Ballet to the People longed for a feminist revision of the ending that would have Jerusha refuse to marry Jervis, as punishment for his dishonest, manipulative behavior. (Or at least keep him hanging.)

On December 10th the show was live-streamed – a first for a New York musical. (Yes, unbelievable but true: the complexities of union negotiations, and handwringing over potential cannibalizing of live audiences, have reportedly deterred Broadway and off-Broadway producers from livestreaming, even as the world’s greatest opera, ballet and Shakespeare companies manage to pull it off.)

Turandot (Metropolitan Opera House)

Christine Goerke and Marcelo Alvarez in Franco Zeffirelli’s production of TURANDOT at the Metropolitan Opera

Dodging the crush of Times Square, fleeing the cyclopean images of airbrushed celebrities hawking the latest must-have gadgets and bling beamed down from the turrets of the Schubert-Nederlander empire, Ballet to the People sought the plush red carpets, twinkling chandeliers, Chagall murals and well-bred calm of the Metropolitan Opera House. Fear and pandemonium reigned onstage however, as armies of Chinese peasants cowered before the icy Princess Turandot in Franco Zeffirelli’s gilded imagining of a celestial Chinese palace.

All the fuss over bronze face in Otello, the Boston Museum’s dress-up-à-La-Japonaise day, the all-Asian casting of Showboat, and the Seattle G&S Society’s Mikado, seems not to have caused anyone helming this production a Nessun-Dorma night. The insane ritual by which the Princess tortures then beheads prospective suitors, the mimsy antics of palace flunkeys Ping, Pang and Pong, the groveling of slave girl Liù, the swaggering of the triumphant Prince Calàf as he claims the Princess like a piece of property – no one’s hollering “Sexism!” or “Racism!” because, well, Puccini.

Amid the visual excess and caricature, the commanding Christine Goerke made the transformation from Medusa to love-struck worshipper entirely believable, her duets with Marcelo Álvarez steeped in honest emotion as the ridiculous tale unfolded. The dashing Álvarez despatched “Nessun Dorma” with a humility and poignancy that Ballet to the People found preferable to the legendary Pavarotti’s booming reverberations.

The pomp and pageantry will be beamed live to over 2,000 cinemas in some 70 countries on January 30th.

Amazing Grace (Nederlander Theatre)

Harriett D. Foy and Josh Young in Christopher Smith and Arthur Giron’s AMAZING GRACE at the Nederlander Theatre (Photo: Joan Marcus)

Had John Newton not written this anthem of faith (so famous that even hardened atheists can sing at least one verse from memory), the tale of his action-packed life, his conversion from slave trader to Anglican minister and prolific composer of hymns, would still make fascinating material for a musical.

18th century English slave traders, in cahoots with an enterprising African tribal princess, face off against a band of brave abolitionists. Newton, the upstart heir to a slave shipment business, is beset by insurgency among the slaves, storms at sea, shipwreck, hostile African tribes, and the disapproval of his fiancée, who becomes a mole for the abolitionists. No shortage of flawed human beings in this tale – and the staging spares us few brutal details in its depiction of the auctioning of human cargo. Yet this remains very much a traditional Broadway musical of the uplifting genre – with a notably cogent historical backdrop, now that human trafficking is recognized as a global security issue.

Superbly executed designs transport us swiftly from upper-class English drawing rooms to tumultuous docks, plunge us into roiling seas, and evoke the oppressive tropical heat of West Africa.

A sterling cast led by Josh Young as John Newton and Erin Mackey as his stouthearted fiancée, Mary Catlett, with star turns by Chuck Cooper and Laiona Michelle as their faithful servants, spin the serviceable score into gold. Cooper’s spellbinding “Where will you go / when there’s nowhere left to run” evokes the plight of refugees everywhere. “Amazing Grace” is reserved for the austere close, and packs an enormous punch – even though its message of trust in an invisible God seems at odds with the musical’s theme of individual responsibility for social justice.

Spring Awakening (Brooks Atkinson Theatre)

This musical debuted like a hurricane in 2006, its pulsating score (by Duncan Sheik) in particular proffering a middle finger to Broadway conventions with songs like “The Bitch of Living.” Adapted from an oft-censored 19th-century German play by Frank Wedekind, the book (by Steven Sater) drives its message home like a sledgehammer: what happens to teens when they don’t receive proper sex education? Unwanted pregnancies. Trauma. Death.

This revival by Deaf West Theatre, imaginatively directed by Michael Arden, stars a youthful cast of hearing and deaf actors. Two of the lead roles are played by deaf actors Sandra Mae Frank and Daniel N. Durant, who sign their lines. Frank is shadowed throughout in an ingenious pas de deux by hearing actor Katie Boeck, identified in the program as the “Voice of Wendla,” while Durant is shadowed by hearing actor Alex Boniello (“Voice of Moritz”). Boeck and Boniello both sing and play the guitar. The entire cast communicates via ASL (American Sign Language) at various points throughout the play; signing becomes a richly evocative element of the choreography. The ardent ensemble includes Broadway’s first wheelchair-bound actor, the dynamite Ali Stroker. These tremendously talented youngsters are so convincing that Ballet to the People, who has not seen the original production, found it difficult to imagine the play being staged any other way. The dual casting, the use of ASL, the new movement opportunities afforded by a wheelchair, all open up new ways of revealing character, and broaden the theme to encompass what director Michael Arden terms a “dark time in Deaf history” when signing was banned in Europe and the U.S. in favor of oral techniques, and when the deaf were stripped of many of their basic human rights.

Veteran actors Camryn Manheim, Marlee Matlin, Patrick Page and Russell Harvard play an array of adult characters, all buffoons or tyrants, all repressive and abusive. The teenagers are – not surprisingly – bewildered, often angry, sad or terrified. The artful direction and triumphant performances cannot compensate for a narrative hewn with blunt instrument nor for the cartoonish rendering of the adult characters.

The score roars out of the starting gate with a stirring teenager’s lament to the “Mama Who Bore Me.” Notwithstanding the purity of the singing and the poetry of the staging, the rest of the songs are about as interesting and original as the Top 10 Rock Anthem Rehashes on ‘American Idol.’

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time (Ethel Barrymore Theatre)

A visit to the cold and soulless new home of the Whitney Museum in the fashionable Meatpacking District – in which Lee Krasner (Mrs. Jackson Pollock) stares across an expansive white space at Mr. Jackson Pollock – preceded The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time on Broadway, whose humming, pulsating white cube of a set comes alive in a manner that Renzo Piano’s new Whitney does not.

This tour de force of visual and sound design draws us into the world as experienced by an autistic teenage boy, the minutiae of city life and everyday interactions distorted and amplified into myriad threats.

Investigating the mysterious stabbing of a neighbor’s dog, the hypervigilant, mathematically gifted young Christopher Boone ends up unraveling a family mystery. To do so he must summon up the courage to travel far from his safe, familiar home base (i.e., all the way to London from Swindon), slaying dragons along the way. We are firmly on his side, even as we sympathize wholeheartedly with the frazzled, well-meaning adults in his life – because we see Christopher not just as a character with a diagnosis out of the DSM IV manual, but as a version of our flawed, lonely, fearful selves, on a heroic mission.

Rosie Benton and Tyler Lea in THE CURIOUS INCIDENT OF THE DOG IN THE NIGHT-TIME at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre

Tyler Lea brings the awkward Christopher vividly to life. Scenes of conflict and reunion between Christopher and his parents (finely nuanced performances by Andrew Long and Enid Graham) are moving, yet the stark geometry of the staging and set design keep this adaptation of Mark Haddon’s prize-winning novel from descending into the maudlin. (No mean feat, considering they’ve also cast a live puppy.)

The Legend of Georgia McBride (Lucille Lortel Theatre)

Dave Thomas Brown as Casey/Georgia McBride in THE LEGEND OF GEORGIA MCBRIDE at the Lucille Lortel Theatre

Drag is not a hobby. It’s not a night job … It’s a protest. It’s a raised fist in a sequined glove.

– Matt McGrath, as drag queen Tracy Mills in The Legend of Georgia McBride

Alternately spouting righteous anger and bitchy humor, in a beaded headdress to rival that of Princess Turandot, Matt McGrath anchors this wildly entertaining musical as a veteran drag queen who initiates an ex-Elvis impersonator into the business.

Casey, played with boy-band charm by Dave Thomas Brown*, has abandoned Elvis’ white leather jumpsuit when his act fails to ignite. He is shoved into a bustier and high heels by Tracy (McGrath), who needs an eleventh-hour replacement for a sidekick who has gone on a bender. Casey plays along because he needs the dough to pay the light bills and to support his pregnant wife, but soon discovers he has an affinity for the gig.

Tracy christens him ‘Georgia McBride.’ It’s only a matter of time before pregnant wife (Afton Williamson, with just the right touch of weary cynicism to counter Thomas Brown’s naiveté) shows up at the dive bar and registers shock at her husband’s new métier.

Thomas Brown looks extraordinarily fetching in sequins and heels, equally scrumptious in jeans and sneakers, and proves a genuine triple threat in both genders. He plays a woman straight, without a hint of parody, and the result is moving. His Georgia McBride avoids the wicked, self-mocking edge of McGrath’s Tracy, and the term ‘drag queen’ seems oddly inapt when Georgia decides impulsively to can the lip-syncing and sing from the heart.

Keith Nobbs doubles impressively as Casey’s impatient landlord, Jason, and Tracy’s intemperate sidekick, Rexy (that’s short for Ms. Anorexia Nervosa).

The zingers fly fast and furiously from playwright Matthew Lopez’s pen, and when we’re not falling off our seats laughing in the cozy Lucille Lortel Theatre, we’re falling in love with these decent, bighearted characters. Lopez’ fundamentally sunny take on the business of drag may disappoint those who seek a more profound exploration of what it means to perform gender. Ignore the shallow storyline and revel in the richly textured performances.

*Hot off the press: Dave Thomas Brown has won this year’s Clive Barnes Foundation award for Theatre.

Ballet to the People do you ever sleep??

🙂 Yes, Deborah, I do! In fact, I have slept through many a Godawful performance, and missed so much of what went down that I was unfit to write a review.