Leigh Donlan reviews an ambitious new book:

I was drawn to Duncan’s philosophy and art in part because it resonated with my own desire to express through dance a vision of a sacred reality that I had glimpsed in transcendent moments of awareness. Clearly, Duncan too had accessed this “inner light” when she wrote like so many great poets, and mystics before her of an ineffable, transcendent source of creation and inspiration. – Andrea Mantell Seidel

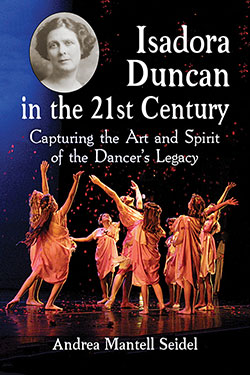

The divine Isadora Duncan has been heralded not only as the matriarch of modern dance but as an ardent defender of the free spirit, a sacred dancer, a mystic and a trailblazer. In her new book, Isadora Duncan in the 21st Century: Capturing the Art and Spirit of the Dancer’s Legacy, Duncan dancer and scholar Andrea Mantell Seidel wants to pass on the wisdom of Duncan’s teachings on dance and life to future generations. Part academic study, part Duncan dance bible, part memoir, Seidel gracefully weaves her own personal tales into the often heady and dense teachings of Duncan – Seidel’s own life an example of these principles at work.

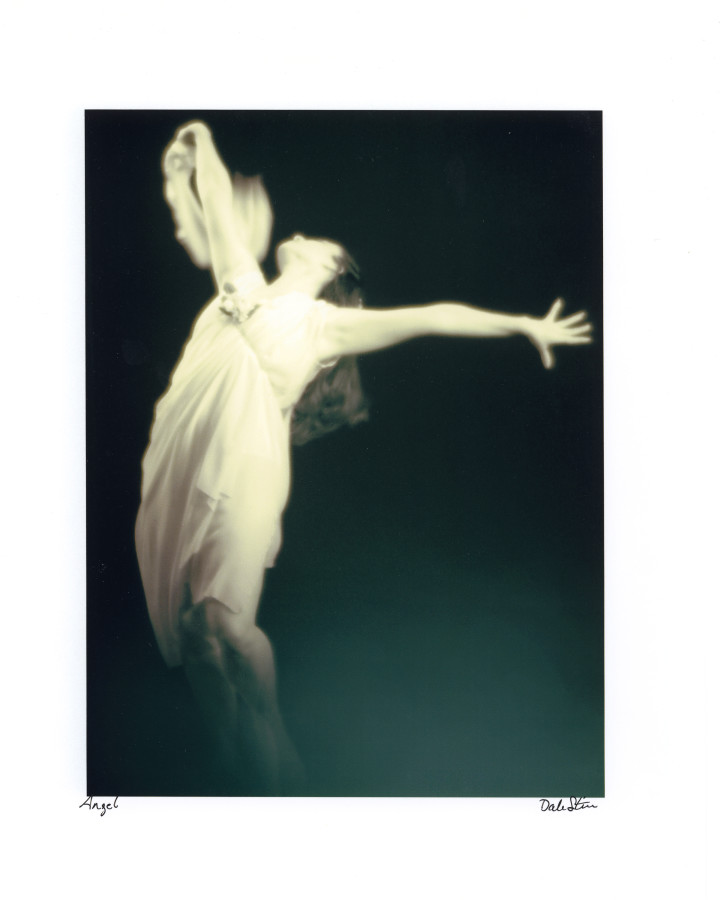

Twelve instructional chapters discuss in great detail how the principles are to be applied in class, rehearsal and performance. These moments are considered sacred rituals rather than events, and they all begin with the breath. Very few sketches of movement or technique accompany the text, as Duncan taught that dance should be accessed through an attained state of “beingness,” from which movement would naturally spring forth. And the intention of this process is to bring the dancer into an awakened state of union with her Higher Self, her body then becoming a conduit for divine energy, capable of expressing the soul. Duncan’s experience with ecstatic states, clairvoyance and premonitions, leads Duncan acolytes to believe that her principles can serve as a gateway for many dancers to experience these altered, higher states of consciousness.

Seidel also provides sage advice to sacred dancers as performing artists. The method requires extensive preparation, practice, commitment and discipline to assure authenticity of the performance. Seidel advises:

While the choreography provides the possibility of experiencing transformative states, the dancer must empower the movement by attuning herself to the “divine continuity which gives all of nature its beauty and life. In this attunement, in this state of “beingness,” the dancer has the possibility of experiencing rapture of the mysterium tremendum [Latin for spirit of “other,” or transcendence] and realizing the artistry of enlightened performance. With this artistry, she becomes the chorus of Blessed Spirits, restoring harmony and equilibrium, affirming life in the midst of darkness, and manifesting the highest ideals.

“The chorus” refers to those of Greek tragedies. Duncan, like Friedrich Nietzsche, from whose writings she was often inspired, turned to the staging of Greek tragedies as a moral alternative to our present human condition. The Greeks were pagans, and rather than deny or attempt escape from their suffering, they used it in staged rituals, thereby facing their worst fears and re-emerging (or so they hoped) as transformed beings. Duncan, in her own writings explained:

At the sublime moment of the tragedy, when sorrow and suffering were most acute, the Chorus would appear. Then the soul of the audience, harrowed to the point of agony, was restored to harmony by the elemental rhythms of song and movement. The Chorus gave to the audience the fortitude to support those moments that otherwise would have been too terrible for human endurance.

After reading chapter after chapter on this Greek influence, however, my enthusiasm for the subject waned. Duncan was surely a seeker with an ambitious desire to return dance to its ceremonial roots – awakening spirituality through movement and ritual. So I couldn’t help but wonder if Duncan had lived longer (she died at 50), would she have continued her studies further back than the Greeks? I do think at some point she might have landed herself in Egypt or India. Because one’s quest doesn’t truly end until you find peace of mind, which Duncan never quite did. Her life was wracked by drama and suffering. And it could be speculated that she died of her own vanity (her long, billowing scarf entangled in a wheel of her convertible Bugatti and snapped her neck.)

But Duncan was on to something – I just think it was only the beginning of her journey. The chakras and Indian mysticism were too quickly brushed over by Duncan, and often her principles feel a bit shallow, as if she hadn’t done enough of her own holy homework, and had relied mostly on the ideas of others. Her principles were Eurocentric yet remarkable for a woman and dancer of her time because she moved to France with her family, a step most Americans of her era (whom she considered lowly money-grubbers) would never consider. And she was brazen in her opinions to an extent that most women of her era, class and background would not have been. But had Duncan lived in this day and age, she would have had a vaster world from which to fashion her principles of transformation through movement.

Anyone considering the path of sacred dance is well advised to do their own holy homework, find their own truth, and “to thine own self be true.”

Where Seidel finally steps out on a limb is in her Epilogue, titled The Dancer of the Future: Onward into the Light. Here, she beckons future generations to heed the call of sacred dance. And though this call feels narrow in scope for those called to the Duncan principles, generations of dancers to come will learn a great deal from Duncan’s vision and precepts, because they not only embody a style of dance that was pioneering at the time, but also embody a crucial way of thinking about the transformative power of all dance. Seidel writes that Isadora prophesied over 100 years ago that

The dancer of the future will be one whose body and soul have grown so harmoniously together that the natural language of the soul will have become the movement of the body… The dancer will not belong to a nation but to all humanity.

And it is in this vein that sacred dancers who do heed this call, deeply and truly, will find what resonates with them. What matters is that dancers remain true to their calling and to themselves.

Previous to this book, Seidel produced multiple Duncan repertoire and technique DVDs – with Julia Levien – in an attempt to preserve Duncan’s teachings. However, this medium proved inadequate in conveying the internal processes required of the dancer. As a thorough explanation of what is required of dancers, both internally and externally, this book is invaluable. It can be used as an introduction for Duncan novices and an in-depth study for the experienced dancer, and a reference for those already versed in sacred dance.

Yet the book is not just for dancers. It is for all movers, all bodies seeking the sacred. It is a lesson in how to move through this world authentically, fully attuned to the possibility of a Higher Self.

I always loved Isadora Duncan, since I was a little girl. I’m 45 now. And just now is that I will start giving classes about this spiritual form of dance, what I called Dynamic Meditation. Where people through movement discover their own light.

I thank God to put this on my way today.

Thank you, Paula. Sounds like you’ve chosen a beautiful path that could be of service to many.

I am envisioning a Global Feminine Spirit, Isadora is my inspiration, Breath is the Center, Qigong, Wuji (woo-gee), standing meditation is my orientation, from the East, Science and Feminism, democracy and rational Thinking, from the West.