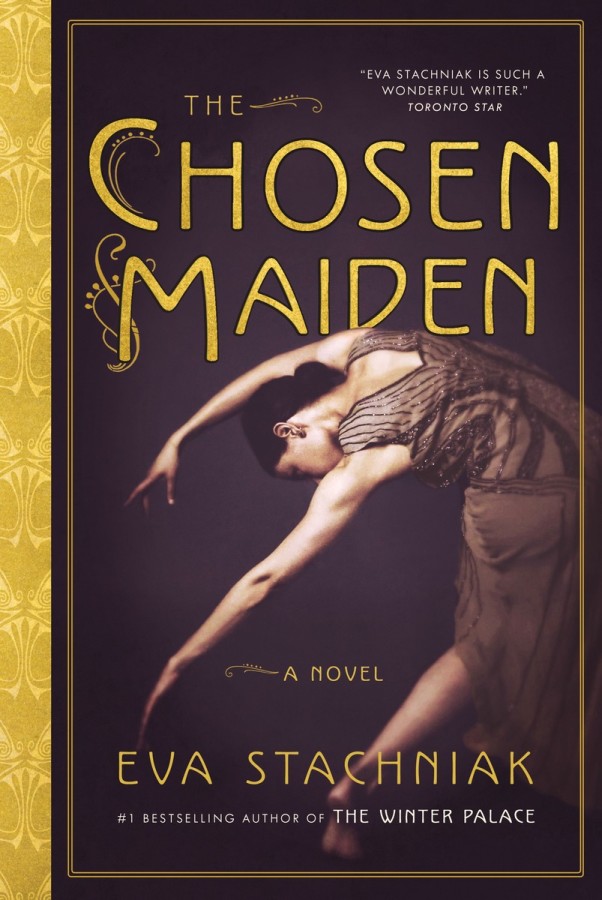

Leigh Donlan reviews a new historical novel about the legendary Nijinska:

The Chosen Maiden doesn’t need to understand what she is doing. She is performing an ancient rite. The desires that push her are those of a being far mightier… the Chosen Maiden is what I want ballet to be. That bold. That powerful. That modern.

– Bronislava Nijinska, as imagined by Eva Stachniak in The Chosen Maiden

Polish author Eva Stachniak’s latest novel, The Chosen Maiden, is a gorgeous body of historical fiction based on the life of Russian ballet dancer-choreographer Bronislava (Bronia) Nijinska, sister of Vaslav Nijinsky. A hefty read of over 400 pages, Stachniak meticulously envisions turn-of-the-century Europe from Bronia’s perspective: growing up on the road with dancer parents; the impact of the First World War on her family, community and the world; the role of art and artists; her relationship with impresario Serge Diaghilev and the many artists of the Ballet Russes. The scope of the novel is broad, yet Stachniak delivers a cohesive and compelling story. Having done much research, she convincingly articulates what she imagines to be the workings of Bronia’s mind, her passion and conviction as an artist, and her ability to endure unspeakable tragedies.

Much of the story is derived from Bronia’s Early Memoirs, which halted in 1914. Stachniak pieced together the rest of her story from the Library of Congress Collection of diaries, choreographic notes, correspondence, photographs, scrapbooks and other memoirs.

The early sections of the book reveal how Bronia lived in the shadow of her brother, the great Vaslav Nijinsky; later sections detail how she managed to come into her own as a highly regarded artist. Throughout the book, we see how men and women are treated differently in the ballet world. Upon their graduation from the Imperial Ballet School of St. Petersburg, both Nijinsky’s were given the complete writings of Tolstoy, whom Vaslav adored earlier in his life. But Bronia was not so taken with Tolstoy, especially when her brother expressed thoughts like “No matter what purpose a woman does – teaching, medicine, art – she has only one real purpose in life, in sexual love.”

But Stachniak reveals that it was precisely being a woman that saved Bronia – while the many peripheral players in the story, particularly the men, were seduced by empty promises of fame and fortune. Stachniak implies that the shallow pursuit of a life of luxury contributed to Vaslav Nijinsky’s descent into madness.

As Bronia came into her own, she began to rebel against the nostalgic qualities of classical dance, against the practice of living in the past. Returning to war-torn Kiev, she gravitated toward other like-minded artists who were also seeking revolution through art, constructing manifestos and plotting:

What if we make art into a cosmic language, an agent of spiritual transformation?

What if – in art – we construct life, not imitate it?

And the war? Whites? Reds? Ukrainians? Germans? Poles? Offensives? Retreats? Victory parades?

What would you do – the running joke goes – if you were playing ball and you learnt that the world would end in half an hour?

We would continue to play ball.

– Bronia, as imagined by Eva Stachniak

In 1919 Kiev, Bronia started her own school – the School of Movement – that offered classical dance “without boundaries.” Her students explored all avenues of movement in addition to drama, reading and writing poetry, painting and stage design. A hopeful Bronia believed that the art of dance would live again, that “… a creator should live only through his creation, not the intoxication of the crowd.” She groomed her students as freethinkers, not as “professional” technicians. Her school was quickly shut down by the Red Army. Her philandering husband left her. And with her ailing mother and two children in tow, Bronia barely escaped Russia back to Paris via Poland, never to return to her homeland again.

The stories of Paris, London and Monte Carlo are just as intriguing, yet of completely different worlds, ones of excess and luxury. Until the war spread and theatres were closed. Funding was cut. Immigrants were looked upon with suspicion. The final chapters read like today’s news feed in America.

Yet The Chosen Maiden – the title taken from the lead role of Vaslav Nijinsky’s Sacre du Printemps, created for his sister Bronia – is very much about surviving unreal times. About finding the strength to continue on after everything is lost. It is about the duty of artists and the revolutionary power of grassroots movements. “The Chosen Maiden, my brother once told me, is a warrior, not a dying swan. She dances to make life possible again.”

Well sadly I’m not in North America so I can’t win a free book but I’ve always loved these designs for Les Biches https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Tcg8_e3Bdw and the Poulenc!

This book is now on my must-read list. I had no idea that Nijinsky had a sister who was also a talented dancer and artist. I can’t begin to imagine how she survived all the hardships and heartbreaks that the reviewer mentioned in her review and how she kept going following her passion for her art. I learned from her wikipedia page that the love of her life, although she did not marry him, was the legendary Russian basse Fedor Chaliapin. I hope that he will make an appearance in this novel as well!

I can’t win a free book either, it’s too bad! The subject is fascinating especially about this period in Europe’s history but you can’t honestly call this a “review”. It’s more of a description of the book by someone who is clearly very into Nijinska. I would find it more interesting to read an assessment by a reviewer who doesn’t feel one way or the other about the subject to begin with.

GMarconi: why would someone who doesn’t care about the subject want to review a novel about her in the first place? I think your definition of a “Review” is very limiting. Just by choosing what aspects of the book to mention, the reviewer has already made an assessment of what is most interesting about it.

Go pick lint out of your carpet. Or write your own review.

The way Anna Kisselgoff sees it, Nijinska’s ideas about dance were shared by George Balanchine “but Nijinska expressed them first.” “In her treatise, Nijinska stands firm against the view that ballet is merely a series of steps and she attacks those who wish to teach it as a fossilized form. Yet she also stands by the classical ballet idiom as a grammar of movement. She expresses appreciation for Isadora Duncan and other modern dancers, but finds their need to create a new idiom unnecessary – a result of “their physical inability to explore fully the classical tradition in which their ideas could have been integrated.”” Imagine if Nijinska was living today and said that about another artist! http://www.nytimes.com/1986/05/11/arts/dance-view-nijinska-in-her-time-was-a-ballet-avant-gardist.html?pagewanted=all