In the span of four days, we were gifted with phenomenal distillations of ballet that has stood the test of time and ballet newly born, from three august companies.

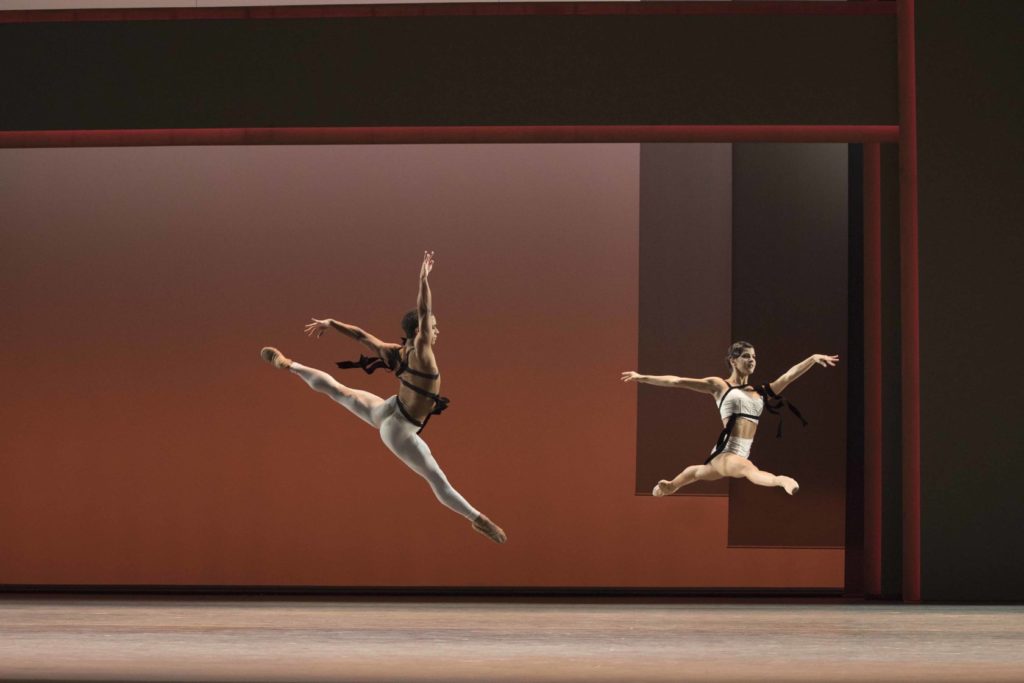

The Royal Ballet’s Tierney Heap in Christopher Wheeldon’s Corybantic Games (Photo: Andrej Uspenski)

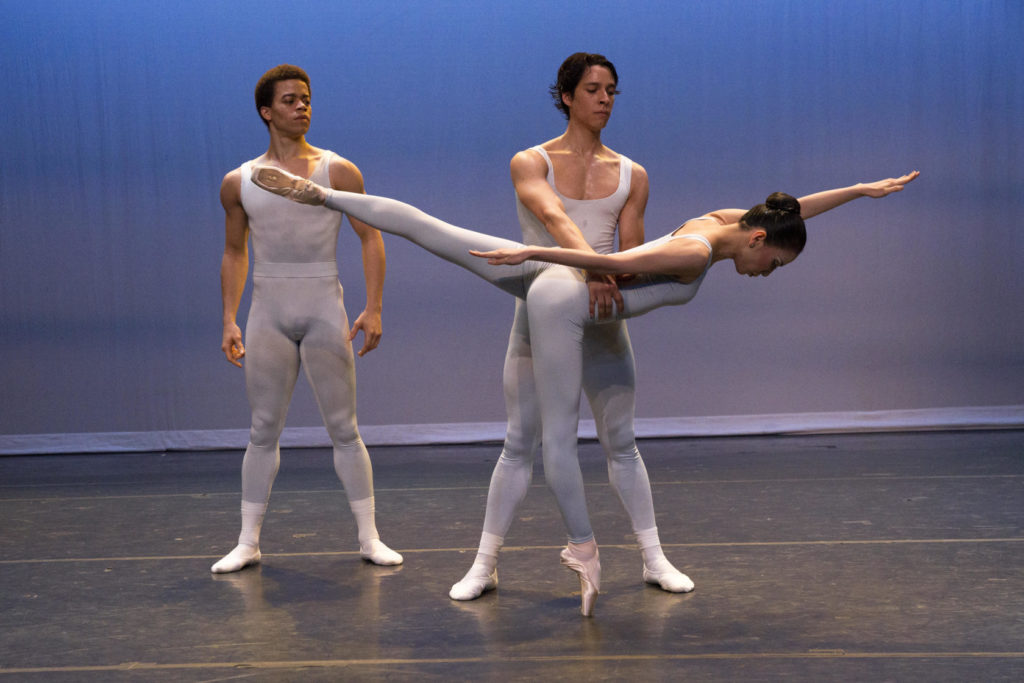

New York City Ballet’s Teresa Reichlen and Chase Finlay in George Balanchine’s Agon (Photo: Paul Kolnik)

On April 24th, New York City Ballet served up three iconic mid- 20thcentury works in its latest Balanchine Black & White program. The next evening, the Royal Ballet broadcast its Bernstein centenary program around the globe, featuring brand new work by Wayne McGregor and Christopher Wheeldon. On their heels, New York Theatre Ballet paid tribute to Jerome Robbins, pairing three of his lesser known gems with a striking Richard Alston world premiere.

A brilliant casting decision paired Maria Kowroski and Abi Stafford in Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco, that sisterhood of the travelling hops on pointe. The mischievous Kowroski charged merrily down every diagonal, luxuriated in every exaggerated stretch and every dramatic plunge off pointe, and bathed us all in her megawatt smile. Stafford maintained a slightly more aloof profile, regal and restrained, but no less authoritative in her etching of lines and in her precision footwork. Their eight seraphic attendants illuminated with dazzling clarity the many off-balance transitions, unfazed by the uncharacteristically subdued orchestra. Bach’s dueling violins lacked oomph.

The war drums in Agon sounded rather distant as well. No matter: the dancers brought all the necessary fire power. The girls invaded the boys’ space, but both sexes came together to sketch out a democratic ecosystem of desire that encompassed intimate relationships of various formats, of which Teresa Reichlen and Chase Finlay’s was the only conventionally heterosexual, monogamous one. Shifting partnerships, and in particular the triangular arrangement between Savannah Lowery, Devin Alberda and Daniel Applebaum, thrilled with their mathematical rigor and surges of tension. The formidable Lowery asserted her free agency before inviting the boys to abet her dare-devilry.

New York City Ballet’s Sara Mearns and Jared Angle in George Balanchine’s The Four Temperaments (Photo: Paul Kolnik)

That was a 1957 creation, and today Christopher Wheeldon has delivered his own take on the contest between the sexes in Corybantic Games, set to Bernstein’s thrilling ‘Serenade, after Plato’s “Symposium.”’ Early on, the men in this community of near-naked Olympian frolickers seemed preoccupied with romancing each other and making intimate homoerotic tableaux; meanwhile the women, in sheer pleated skirts, gambolled innocently through the fields, rejoicing in sisterly friendships with apparently no thoughts of sex whatsoever.

Just as the dreadful unfairness of this asymmetry started to sink in, Wheeldon served up three intimate pas de deux that unspooled simultaneously in three pools of light. Matthew Ball with William Bracewell, Beatriz Stix-Brunell with Yazmine Naghdi, and Lauren Cuthbertson with Ryoichi Hirano traced mesmerizing portraits of gay, lesbian, and heterosexual love, respectively, to Bernstein in a meditative, stately mood. It sounds corny but was visually stunning and emotionally moving. Wheeldon then pivoted to a new era of female power – with the redoubtable Tierney Heap at the top of the heap, orchestrating frenetic, kinetic rituals in which men and women (having abandoned the skirts) competed as equals. Throughout, Wheeldon’s movement invention never flagged.

The Royal Ballet’s Marcelino Sambé and Mayara Magri in Wheeldon’s Corybantic Gamtes (Photo: Andrej Uspenski)

Heap’s tour de force recalled that of Megan LeCrone’s ‘Choleric’ variation in The Four Temperaments, the final offering on the Balanchine triple bill. Dark eyes flashing, LeCrone set in motion the machinery whose constituent parts had been introduced in the preceding theme and variations. Notable among them were the elegant and mysterious Lydia Wellington and Andrew Scordato in the first theme; Sara Adams and Aaron Sanz, glorious and precise in the zippy second theme; and Miriam Miller proudly promenaded by Cameron Dieck in the third. The soulful Sean Suozzi made the most of the jazz elements in ‘Melancholic,’ though his upper back and shoulders lacked the pliancy that has distinguished predecessors in the role. Jared Angle made barely a pixelated image next to the sharply etched ‘Sanguinic’ of Sara Mearns.

New York Theatre Ballet’s Steven Melendez, Joshua Andino-Nieto and Mayu Oguri in Jerome Robbins’ Concertino (Photo: Richard Termine)

Echoes of the second pas de trois in Agon resonated in Jerome Robbins’ 1982 Concertino, one of three timeless chamber works that opened New York Theatre Ballet’s REP program last week. The sleek Mayu Oguri danced like she ate nails for breakfast, striding insolently on pointe; gestures of the hands like windshield wipers and the moody, astringent Stravinsky Concertino for String Quartet suggested an existential road trip in the rain with stalwart henchmen Joshua Andino-Nieto and Steven Melendez.

Septet for five dancers and two Stravinsky-devouring pianists showed Robbins in a more courtly, playful mood. With their clean, unfussy technique, the Theater Ballet dancers wittily subverted some ballet fundamentals with feet crossed in a turned-in fifth position, and a casual dive to the floor in penché that finished with a hand rooted to the floor. A signature movement, the unfurling of a leg in high développé en relevé often lingered, leaving traces of wistful emotion in the air.

Rondo, a 1980 pas de deux to Mozart, unearthed quiet drama, with hints of Barocco, in the ties that bound two women – the sunny, angelic one (Elena Zahlmann) whom you felt you could read like a book, the other (Amanda Treiber) more mysterious and quirky. Zahlmann evinced a momentary fascination with the onstage pianist (Michael Scales), but found a stronger affinity with her female partner.

New York Theatre Ballet in Richard Alston’s The Seasons (Photo: Richard Termine)

The tiny but distinguished Theatre Ballet occupies a rarefied niche in the ballet world, burnishing rarely seen chamber works from the past and also nurturing emerging choreographers, many of them women. It also provides an American home to U.K.-based Richard Alston, who for this program wrestled with The Seasons, a sparse, knotty John Cage score. The very fine, explosive Melendez called forth a merciless Winter while successive pairings and small groups of men and women made like melting water running down from glaciers (to the rippling piano), flew across the stage then tumbled, like wind stripping trees of foliage. Couples entertained the briefest of courtships as if acknowledging that these, too, shall pass like the seasons. The less-is-more dance vocabulary offered a refreshing contrast to the busyness of so much contemporary ballet. One cocked arm with elbow raised and fingers lightly touching the shoulder made an assertive signature gesture – like an eagle with one broken wing, vulnerable but still noble. At the close, Melendez banished the ensemble and sunk to the floor, forehead to ground, and embraced the earth with a ceremonial sweeping of the arms. A gesture that pierced the overwhelming bleakness and rekindled a sense of optimism for the future of our planet.

The Royal Ballet’s Federico Bonelli, Sarah Lamb & Calvin Richardson in Wayne McGregor’s Yugen (Photo: Andrej Uspenski)

This optimism was echoed on a grander scale in Wayne McGregor’s sublime Yugen for the Royal Ballet, set to Hebrew psalms scored by Bernstein for the cathedral at Chichester. Sung for these performances by the Royal Opera House chorus, with plaintive beauty, the score appears to have put McGregor in an unusually tranquil mood. Dancers in simple, loose garments emerged from tall vitrines of light designed by ceramicist Edmund de Waal. There was the faintest narrative suggestion of the coming of age of a vulnerable young man (Calvin Richardson) and wise figures who stepped in to guide him. The divine Sarah Lamb was one of them, but it looked like she died at the end and was carried off to heaven in a scene as austere and affecting as the final moments of Balanchine’s Serenade. A group of men appeared to drape Richardson in armor, preparing him to face some vague danger that threatened the community – a drought perhaps, or an imminent invasion. Movement was liquid, silky, yearning but disciplined and pared back. At the end, Richardson exploded into a classical double air turn – the culmination, perhaps, of his initiation into this mysterious tribe. As in Serenade, these narrative elements carry no fixed meaning but are open to an exhilarating range of interpretations. It was enough to turn an atheist into a believer. And a ballet skeptic into an addict.

– Carla Escoda, 6 May 2018

The Royal Ballet’s Joseph Sissens and Akane Takada in McGregor’s Yugen (Photo: Andrej Uspenski)

Artists of The Royal Ballet. in McGregor’s Yugen (Photo: Andrej Uspenski)

Engaging write up !

A few thoughts:

I’m in sync with the notion of

‘The less-is-more dance vocabulary offered a refreshing contrast to the busyness of so much contemporary ballet.’

Often the master’s craft is the ability to pare away all the myriad possibilities down to a small set that reveals more easily a bare essence. There’s a time and place for busyness, but those times when we see something convey so much from so little.. oh, it grabs a person !

“Bach’s dueling violins lacked oomph.”

I didn’t see the performance (obviously !), but IMHO The violinists probably were limited by the nature of Bach’s composition. The typical counterpoint/polyphony of a Bach composition demand that performers ‘stay the course in measured fashion’ so as not to ruin the meshing of the voices together. It’s beautiful stuff, but it was for later composers to bring the greater expression of passion into music. YMMV !

Wise words, Thorick.

Re the NYCB orchestra on that night, esp. the violins, it was really the lack of volume that struck me, rather than any absence of passion. The sound that night seemed muted, a little too hushed.