“Is everybody in the world going to die before someone finds the answer?” asked reluctant vampire-slayer Dr. Robert Morgan, played by Vincent Price in the classic horror film The Last Man on Earth. Morgan battles a mysterious pandemic that turns humans into vampires – a premise that evoked mid-20th century paranoia over the spread of Communism and the fear that alien sleeper cells would destroy civilized society.

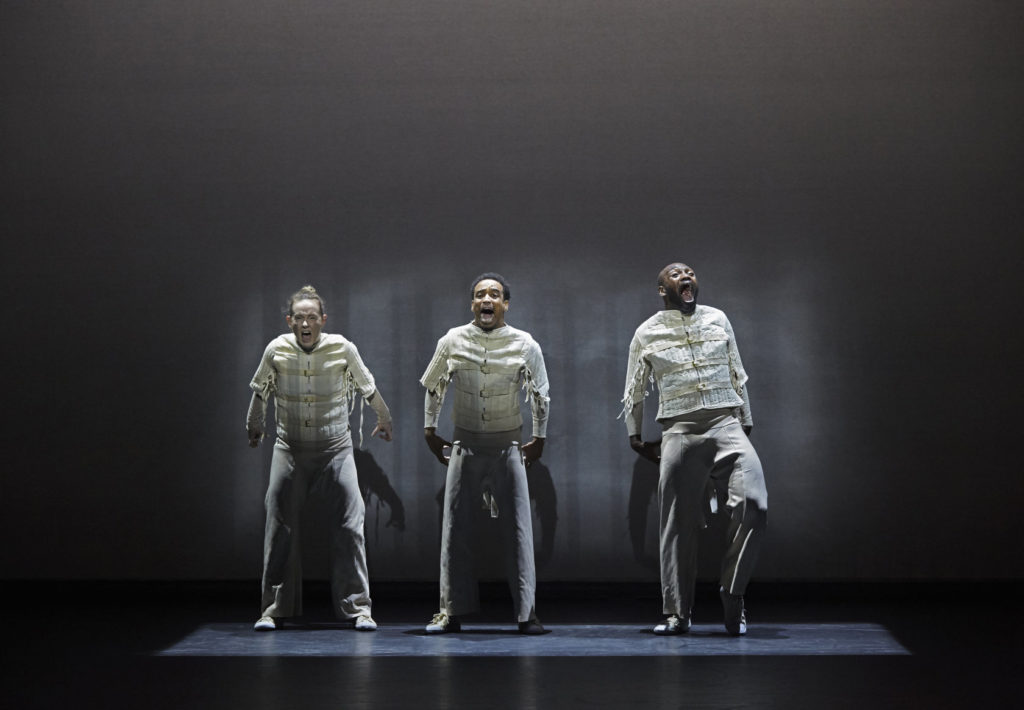

Boy Blue in Blak Whyte Gray by Michael “Mikey J” Asante and Kenrick “H2O” Sandy (Photo: Carl Fox)

Two weekends ago, that chilling line embedded in the eerie score of Blak Whyte Gray – a hip-hop theatre piece by East London-based Boy Blue that blew in to Lincoln Center’s Mostly Mozart Festival – just happened to capture the despair and outrage over the pair of mass shootings in Dayton, Ohio, and El Paso, Texas. In a nation that is averaging more than one mass shooting per day, call that just another weekend in America.

The piece opened with a trio of dancers – the riveting Gemma Kay Hoddy, Nicole McDowall and Ricardo Da Silva – rooted to the stage as the score unleashed round after round of noises that reverberated like gunfire or jolts of electricity. Under assault from the soundtrack and trapped in a small square of light, the dancers recoiled, convulsed and shuddered in epic displays of locking and popping. Strapped into jackets that resembled medieval padded armour, with downlighting that cast their eye sockets in deep shadows, these figures remained resolutely enigmatic. Though at one point they raised their hands to their temples, as if clutching at goggles, and peered around cautiously. Perhaps they were fighter pilots whose aircraft had been shot down over enemy territory. Sputtering attempts to escape their torture chamber proved futile.

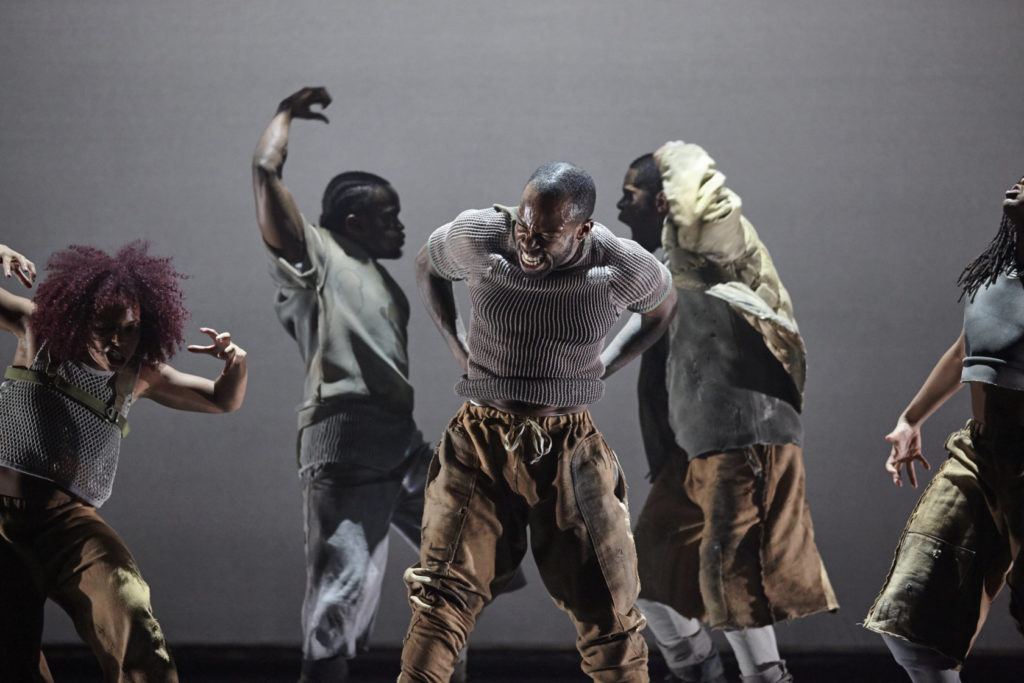

That electrifying opening section, titled Whyte, turned to Gray as the rest of the ensemble glided in from the wings on their backs, propelled by feet and hands pushing against the floor. They could have been a SWAT team swooping in to liberate the trio from Whyte, wielding the power of krump with its emphatic jabbing, stomping, chest thrusting and arms flashing like samurai swords.

Hip hop imagery of slavery and oppression yielded to hip hop as ebullient self-expression, the choreography streaked with movements from martial arts, acrobatics, boxing, and contemporary dance. The score, which mostly pulsated, hissed and clanged in Whyte, now embraced the sounds of wind chimes and African drums. The dancers saluted each other by bumping raised forearms and roamed the stage as if to reclaim ancestral lands. Huddled in a defensive clump, they brandished invisible rifles and tossed out the occasional imaginary grenade as they scanned the audience for marauders.

Boy Blue in Blak Whyte Gray by Michael “Mikey J” Asante and Kenrick “H2O” Sandy (Photo: Carl Fox)

The final element of the triptych, titled Blak, portrayed the rise of a leader – an inchoate figure who was rescued and nurtured by the community. When the ensemble first encountered Dani Harris-Walters, he was on his knees, head bowed; all we saw from the audience were his naked shoulders, arms and upper back. The tortured twisting and heaving of his musculature was transfixing, conveying the anguish of a faceless outcast.

The ensemble propped this shaky figure up. They endowed him with strength (teaching him to “zip up” his core) and heart (forming their hands into the shape of a heart). And they projected their hopes onto him. Once he had blossomed into a hip hop warrior, they wrapped him in a flowing red cloth, in a kind of coronation ritual.

The solo work by Harris-Walters was stunning – defiant and fluid, it recalled Bruce Lee’s famous injunction to “be like water.”

While the mood in Blak was mostly joyful – especially in the coda in which these splendid dancers flaunted their best moves in a good old-fashioned hip hop battle – some elements hinted at the rise of demagoguery. That long red cloth that spilled across the entire width of the stage evoked a river of blood. And the capriciousness with which the ensemble chose their hero and the intensity of their hero worship summoned up the minefields of our modern-day political system.

Boy Blue in Blak Whyte Gray by Michael “Mikey J” Asante and Kenrick “H2O” Sandy (Photo: Carl Fox)

Co-creators Michael “Mikey J” Asante (music) and Kenrick “H2O” Sandy (dance) have said that Blak Whyte Gray reflects preoccupations with Black Lives Matter, the climate in Britain post-Brexit vote, the “tension between apathy and action,” as well as more personal journeys. The work, with its allusions to slavery, colonialism and revolution, seemed to find catharsis in the search for identity. Blak, as it turns out, isn’t about the quest for a savior and doesn’t end with a coronation, for the prince merges into the ensemble. Rather, hip hop eventually sets each dancer free to explore their roots and their own unique gifts.

This idea was abetted by masterful ultraviolet lighting effects (courtesy of lighting designer Lee Curran) which revealed luminescent war paint on faces and bodies and on rough-hewn white masks that descend from the rafters – a nod to tribal origins, and a reminder that heritage is often more complex than we assume.

Boy Blue is not alone in deploying the language of hip hop to create theatrical works with social and political messages. But Blak Whyte Gray packs an uncommon punch. It returned to New York courtesy of the Mostly Mozart Festival, after a sold-out run in 2018. The political environment on both sides of the Atlantic has only turned more corrosive since then. In an era in which fear of the “other” has been stoked by power-mad con men, Blak Whyte Gray should jolt the complacent and the cynical.

– Carla Escoda reviewed Blak Whyte Gray at the Gerald W. Lynch Theater at John Jay College on Thursday, Aug. 1, 2019.