It was a rare treat to watch a handful of Royal Ballet stars in the intimate surroundings of New York’s Joyce Theater; even better to catch them in play dates with their friends from New York City Ballet, American Ballet Theatre and New York Theatre Ballet.

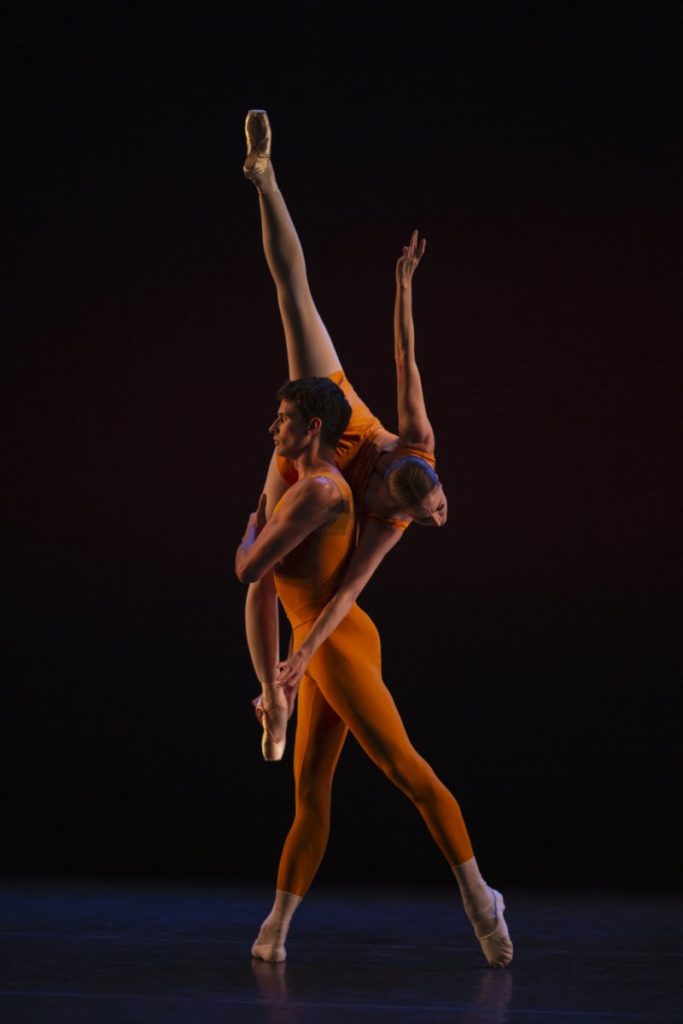

Calvin Richardson and Joseph Sissens in Christopher Wheeldon’s Within the Golden Hour(Photo: Maria Baranova)

Four programs were individually curated by artistic director Kevin O’Hare, by principal dancers Lauren Cuthbertson and Edward Watson, and by dancer-designer Jean-Marc Puissant. I caught two of the four, and while I expected potluck, I also expected the dances to be in conversation with each other in some manner. The seemingly haphazard choices in Programs A and C left me to wonder if somehow B and D tied it all together.

The dancing, of course, was impeccable, as was the desire to honor past and present in the Royal’s history.

Gemma Bond’s Then and Again (Photo: Maria Baranova)

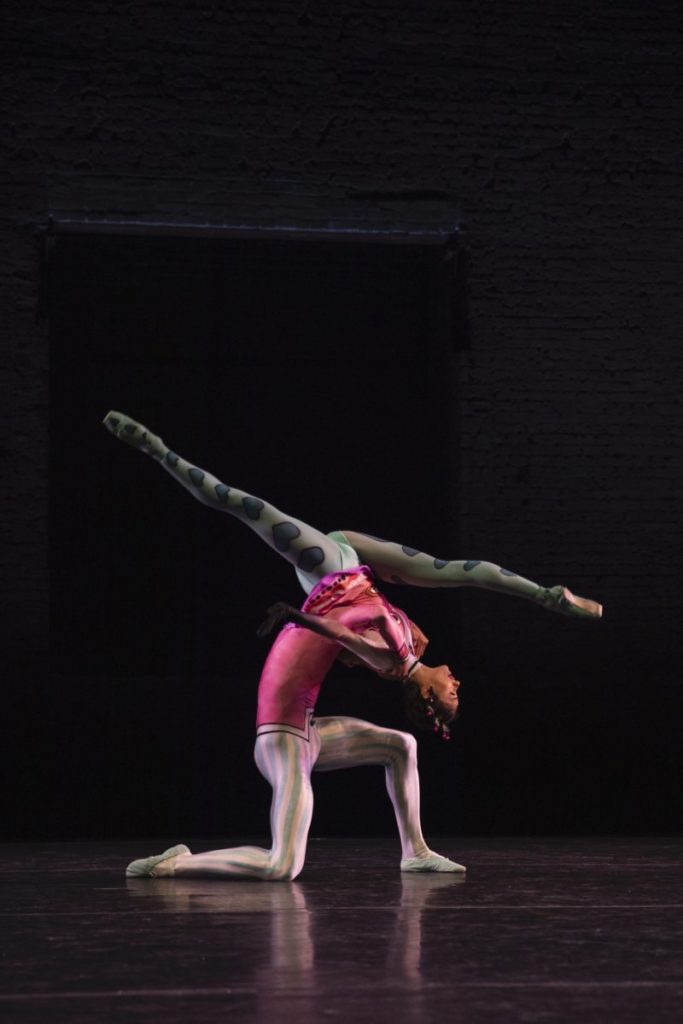

In a nice touch, the work of Gemma Bond, who has danced with both the Royal and ABT, showed up – twice. The piece I caught was a revival of Then and Again. This was populated by a windswept crew of ABT women in identical shift dresses, who dashed about on mysterious errands punctuated by brief encounters with the poetic Thomas Forster and the spirited Erez Milatin. Anabel Katsnelson made a particularly vivid impression, diving fearlessly into her partner’s arms, and attacking her work with both precision and daring. In one of many lovely partnered moments, Katsnelson sank eloquently over her pointes, as Forster slipped his hands under her arms to ease her descent. The women would frequently cock their elbows and lift their arms with palms facing outward in a puzzling gesture that conveyed vulnerability, even as they fired off crisp piqués and emphatically grounded arabesques. Alfredo Piatti’s 12 Caprices for Solo Cello proved eminently danceable, but monotony kicked in after five or six.

Anabel Katsnelson in Gemma Bond’s Then and Again (Photo: Maria Baranova)

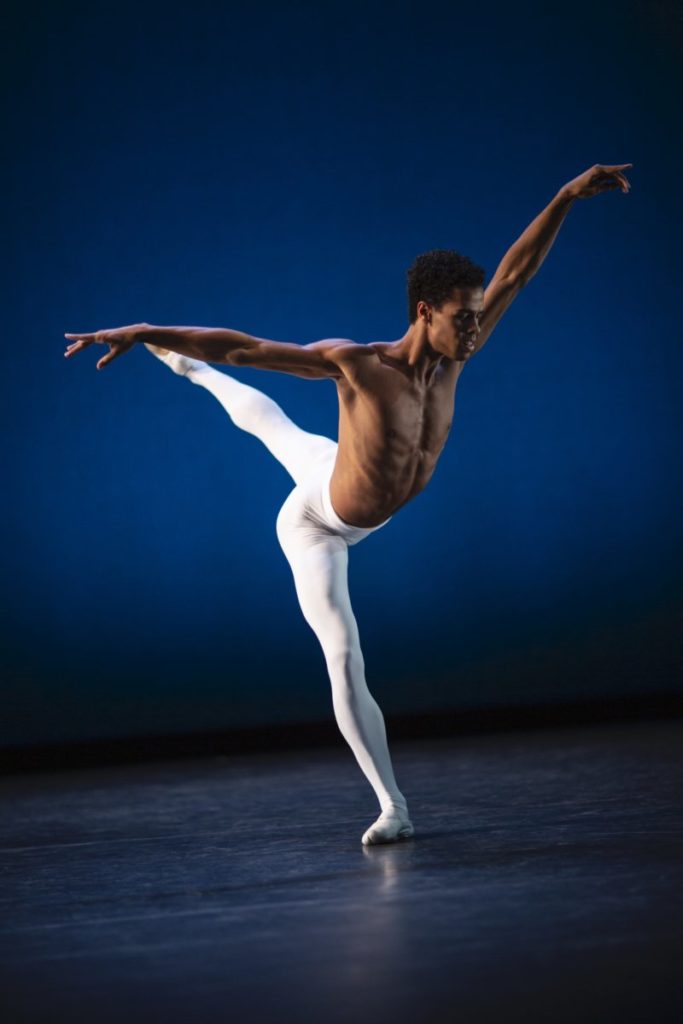

Joseph Sissens in Charlotte Edmonds’ jojo (Photo: Maria Baranova)

Also waving the flag for that elusive tribe of female choreographers was Charlotte Edmonds, who in 2015, at the tender age of 19, was appointed the first Royal Ballet Young Choreographer. Edmonds arrived with a solo which she had created last year on Joseph Sissens, titled jojo. Sissens demolished this fusion of street, Latin, contemporary and ballet, set to the irresistible groove of Chinese Man’s ‘Pandi Groove.’ He looked like he was having a whale of a time. There wasn’t much daylight between this and the increasingly sophisticated choreography that’s being made for television dance competitions. Maybe that is the hook that is going to lure younger audiences into the opera house. I vote for more.

That said, I suspect we did not get the best work of either Edmonds or Bond.

Ditto for Royal Ballet stalwarts Christopher Wheeldon and Liam Scarlett who were represented by polished yet bland duets from Within the Golden Hour and Asphodel Meadows, respectively, stuffed with intricate partnering and decorous cavorting, signifying nothing. Pianist Kate Shipway’s affinity for Poulenc’s luminous piano concerto in D minor kept us from nodding off in Meadows, and Jasper Conran’s shimmering finery for Golden Hour was a welcome update from the drab costumes sported by San Francisco Ballet when that company performed the piece a few seasons back.

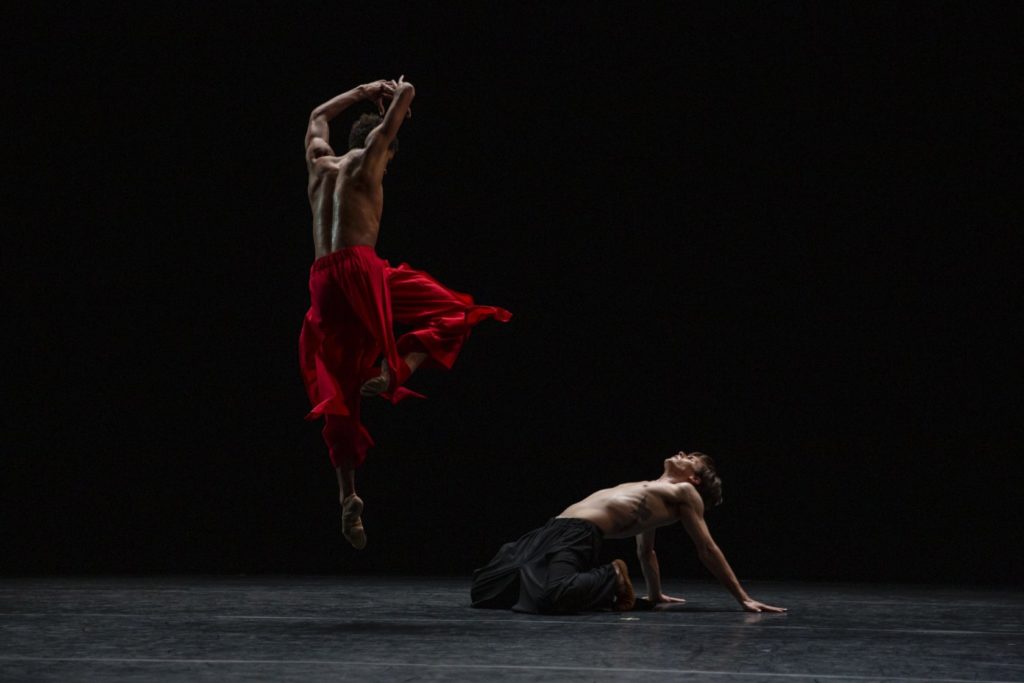

Joseph Gordon (foreground) and David Hallberg in Maurice Béjart’s Song of a Wayfarer (Photo: Maria Baranova)

We did get the best of Maurice Béjart, however, in his Song of a Wayfarer. Created on Nureyev and Paolo Bortoluzzi in 1971, it was performed at the Royal by Nureyev and Anthony Dowell in 1975. Otherwise Béjart barely figures in the Royal’s rep. Nureyev biographer Julie Kavanagh wrote of Ninette de Valois, whose influence at the Royal was felt long after she retired from the directorship in 1963:

She was furious that Anthony Dowell, “a truly great and dedicated artist,” had profaned himself by appearing with Rudolf in Songs of a Wayfarer. “I would not enter into a discussion over the pretentious Béjart work,” she told [critic Nigel Gosling], “except to quote Nureyev, ‘We did everything up to conceiving on the floor.’”

I must have missed that moment at the Joyce.

Rather, City Ballet’s Joseph Gordon in the Nureyev role and ABT’s David Hallberg in the Bortoluzzi gave us a solemn and affecting study of a young man and his enigmatic mentor, or perhaps a darker force of nature.

The majestic and moving Mahler song cycle was more profoundly explored by Norman Walker in a piece roughly contemporaneous with the Béjart, set on the Philippine danseur noble Nonoy Froilan. Walker’s Wayfarer hewed more closely to Mahler’s libretto, which tells of the anguish of a young man whose girlfriend runs off to marry someone else. Béjart’s protagonist, on the other hand, appeared to be lost rather than lovelorn.

Joseph Gordon and David Hallberg in Maurice Béjart’s Song of a Wayfarer (Photo: Maria Baranova)

Gordon was stirring and unaffected in the role, powerful and secure in his technique. Hallberg appeared somewhat gaunt in contrast. The exquisite articulation of his feet has not diminished, nor has the remote beauty of his gaze, but his technique was a little shaky. Nevertheless, he struck an imposing air as the shadowy figure who ultimately leads the young man to an unknown fate. The movement vocabulary for both dancers was subdued and striking in its minimalism, with only a few brief instances of pelvic grinding and buttocks jiggling to remind us of the more familiar Béjart.

Lauren Cuthbertson and Nicol Edmonds in Kenneth MacMillan’s Concerto Pas de Deux (Photo: Maria Baranova)

Affectionate tributes to Frederick Ashton and Kenneth MacMillan were inspired – above all, the slow movement from MacMillan’s Concerto. Lauren Cuthbertson and Nicol Edmonds traced sublime geometries while Kate Shipway’s pensive solo piano revealed subtle glories in Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto No. 2. They could have put that pas de deux on repeat for the entire duration of the festival and audiences would likely have camped out for days.

Joseph Sissens in Frederick Ashton’s Dance of the Blessed Spirits (Photo: Maria Baranova)

Ashton was represented by two all-time hit solos.

Dance of the Blessed Spirits from Orpheus and Eurydice was blessed with Joseph Sissens’ purity of line, in a performance that recalled his stellar outing in the Merce Cunningham Night of a Hundred Solos back in April.

Romany Pajdak in Frederick Ashton’s Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan (Photo: Maria Baranova)

Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan did not get off to a promising start, with Romany Pajdak looking as stiff as the red wig pinned to her head. Pajdak tackled the movement with more authority than passion, hitting poses with a balletic exactitude that seemed hardly “in the manner of.” Her dancing transformed, however, after the lovely business with the long flowing scarf that sent her flying into the wings. When she returned, her fists full of rose petals, she danced with a new lightness and abandon, and a faraway look in her eyes.

Was her disappearance with the scarf meant to summon up Isadora’s tragic death? (Isadora was killed in a freak accident in which her scarf got tangled in the hubcaps of her open car and strangled her.) As Pajdak re-emerged, strewing rose petals with every flying hop and whirling jump, she evoked a wraith, possibly Isadora’s ghost. It was an effective staging and a satisfyingly eerie interpretation, underscored by pianist Kate Shipway’s ardent handling of the Brahms.

Romany Pajdak in Frederick Ashton’s Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan (Photo: Maria Baranova)

The snippets from MacMillan’s Elite Syncopations were perfection in their sly wink-and-a-nod bravura. Ian Spurling’s cartoonish lycra bodysuits that look like they’d been spray-painted on, remain as kooky as ever, and the only thing missing, dance-hall-atmosphere-wise, was the live band onstage. Romany Pajdak and Joseph Sissens were flat-out adorable in the ‘Ragtime Nightingale’; she kept him busy figuring out how to maneuver her torso around the barrier created by her extended leg in various positions. ABT’s Cassandra Trenary, slinky but self-deprecating, nailed the ‘Hot-House Rag.’ The brash Marcelino Sambé in ‘Friday Night’ made those explosive jumps that change direction in mid-air look like a breeze. The divine Sarah Lamb and foppish Nicol Edmonds danced ‘Bethena: a Concert Waltz’ with buttoned-up refinement, no outward hint of sex other than her sassy pink boater tilted at a dangerous angle.

Romany Pajdak and Joseph Sissens in Frederick Ashton’s Elite Syncopations (Photo: Maria Baranova)

Marcelino Sambé (foreground) and Joseph Sissens in Frederick Ashton’s Elite Syncopations (Photo: Maria Baranova)

Calvin Richardson and Sarah Lamb in Frederick Ashton’s Elite Syncopations (Photo: Maria Baranova)

Sex was front and center, and every which way, in Wayne McGregor’s Qualia Pas de Deux for Lamb and Edward Watson. “They are going at it,” read my notes. I had a feeling Ninette de Valois would not have approved. In Y-fronts and singlets, the sinewy couple grappled and engaged in some anything-you-can-do-I-can-do-better, like seeing who could lift their leg higher in à la seconde. (That ended in a tie.) Apart from one off-putting move in which Watson pressed his hands into the floor and hyperextended his elbows, the splaying of limbs that often seems pointless in McGregor’s larger, messier, bloodless works, mesmerized here. There were some very cool lifts and spins. The pulsating score was by someone who goes by the name of Scanner – possibly because his soundscapes involve the use of police scanners. The whole thing was engineered with an admirable precision and structural economy.

Edward Watson and Sarah Lamb in Wayne McGregor’s Qualia Pas de Deux Photo: Maria Baranova)

Edward Watson and Sarah Lamb in Wayne McGregor’s Qualia Pas de Deux Photo: Maria Baranova)

McGregor’s Obsidian Tear was also on tap in an excerpt featuring Joseph Sissens and Calvin Richardson. The dynamic between this pair was mystifying – perhaps in the context of the larger work (which I’ve not seen) we could have deduced whether these two were in a power struggle, a Tinder meet-cute, or enacting some peculiar fraternity hazing ritual. Bare-chested and in flowing paneled trousers, they slouched, they rolled their shoulders, undulated their torsos, rubbed their thighs and snapped their fingers to the wailing violin of Esa-Pekka Salonen’s “Lachen Verlernt.”

Joseph Sissens (in the air) and Calvin Richardson in Wayne McGregor’s Obsidian Tear (Photo: Maria Baranova)

As a teaser for the full-length piece, this glimpse of Obsidian Tear delivered the goods. Yet a sample from McGregor’s Chroma, Yugen, or AfteRite might have proved just as juicy and somewhat less baffling.

– Carla Escoda reviewed Ballet Festival at the Joyce Theater Programs A and C on August 6 & 13, 2019

Mah’vlous Norman Walker. Gertrude Shur turned to me while we watched him take class 57 years ago, and pressing her lips together into a thin line, said, “Norman fears neither time nor space.” Thanks for the reminder!

So funny!

And what a small world the dance world is, Toba.

So much of this programming was icky-from Elite Syncopations to the master-slave routine in Obsidian Tear. Then there’s the human trafficking angle in that bizarre Béjart thing. That quote from Ninette de Valois was hilarious but Songs of a Wayfarer wasn’t just pretentious, it was disturbing.

I get that ballet like any art can explore the darker human impulses. But there is a line between art and trash. Reading your reviews I think you know where that line is-most of the time. You got it wrong here.

There’s a line?

I missed the human trafficking angle, too. Hmm.