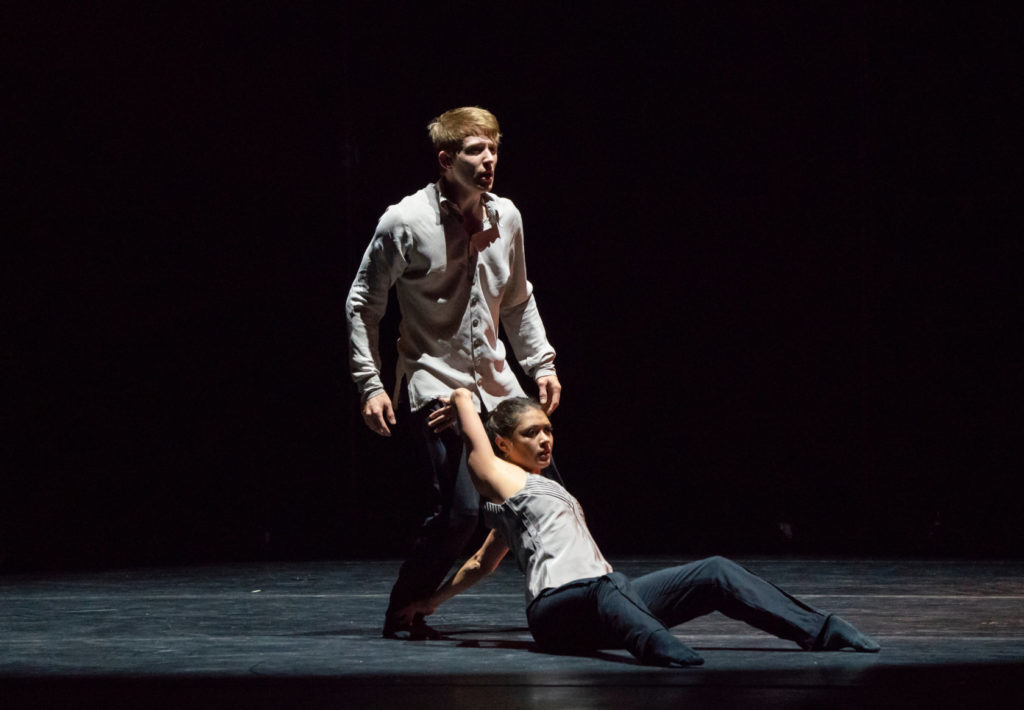

An evening of largely uplifting and celebratory dance at New York City Center’s Fall for Dance opened with a bleak portrayal of intimacy by Crystal Pite.

Elliot Hammans and Alicia Delgadillo of Hubbard Street Dance Chicago in Crystal Pite’s A PICTURE OF YOU FALLING (Photo: Stephanie Berger)

This finely wrought duet, heroically delivered by Elliot Hammans and Alicia Delgadillo of Chicago’s Hubbard Street Dance, traced the chance encounters that led up to an affair, and its dissolution. (Is there a romance that could withstand the pitiless surveillance of lighting designer Robert Sondergaard’s array of lights on tall masts surrounding the stage, harsh followspot and flashes like those from a paparazzi’s camera?)

The duet’s title, A Picture of You Falling, is lifted from spoken text, delivered in deadpan by British actress Kate Strong and sprinkled throughout the piece, that provided signposts to the action and settings. The spoken words felt superfluous on top of the score by Owen Belton, a moody assemblage of industrial sounds, and the spiraling, shuddering movement that owed as much to hip hop as it did to ballet and contemporary dance.

Misty Copeland in Kyle Abraham’s ASH (New York City Center Commission | World Premiere)

(Photo: Stephanie Berger)

A similarly bleak landscape was conjured up in the evening’s lone solo by Kyle Abraham for Misty Copeland, titled Ash. The eerie minimalist score by Ryuichi Sakamoto and Alva Noto pinged and scraped and bounced off a stage stripped to bare concrete walls and towering lighting rigs. Copeland picked her way across this hostile terrain, zigzagging delicately, serenely, intently, with small stabbing movements of her steely arced feet and brief outbursts of skimming jumps. Smashingly clad by Reid Bartelme and Harriet Jung in a dull gold velvet leotard that was sheathed in a layer of netting and gathered at hips and shoulders, Copeland in her mercurial explorations suggested a Psyche butterfly, emerging from a powdery gold chrysalis. Like this pale-winged species that hovers low to the ground, she exuded a restrained, unshowy glamour. Against the stark visual and aural surroundings, she performed an idea of grace sprung from the ashes of some cataclysmic ruin.

By contrast, the two big ensemble works on the opening night program, from South Africa’s Vuyani Dance Theatre and America’s Caleb Teicher & Company, brimmed with explosive energy and celebrated individual and group virtuosity in loose episodic formats.

Vuyani Dance Theatre (South Africa) in Gregory Maqoma’s RISE | US Premiere

(Photo: Stephanie Berger)

Vuyani’s creative director and founder Gregory Maqoma honored the individuality of his dancers in Rise, fueled by a soundtrack of recent hits by Drake, John Legend and Labrinth, among others. Billie Holiday’s ‘Strange Fruit,’ a searing protest song about lynchings in the American South, occupied a league of its own. To this formidable mix, the company of 11 dancers flaunted an impressive repertoire of modern dance and hip hop moves, punctuated with beaten jumps from ballet, Afro-Caribbean dance rhythms, social dance and acrobatic moves, tossed off with streetwise cool. From a perch upstage, the boyish Musa Motha played DJ and appeared to direct the dancers, before joining them. While he blended effortlessly into the ensemble, the quality of his dancing stood apart, for he used a crutch as an aid, having lost one leg at a young age to amputation. Captivated by how Maqoma deploys his dancers, I continued to wonder why there aren’t more choreographers working with dancers whose movement is aided by equipment.

Musa Motha and Thabang Mojapelo in Gregory Maqoma’s RISE (Photo: Stephanie Berger)

I’ve read about Maqoma’s other work with overt narratives that engage with specific historical struggles. Rise felt like more of a dance party rather than a work of dance theatre, and I’d have liked to see that side of the company as well.

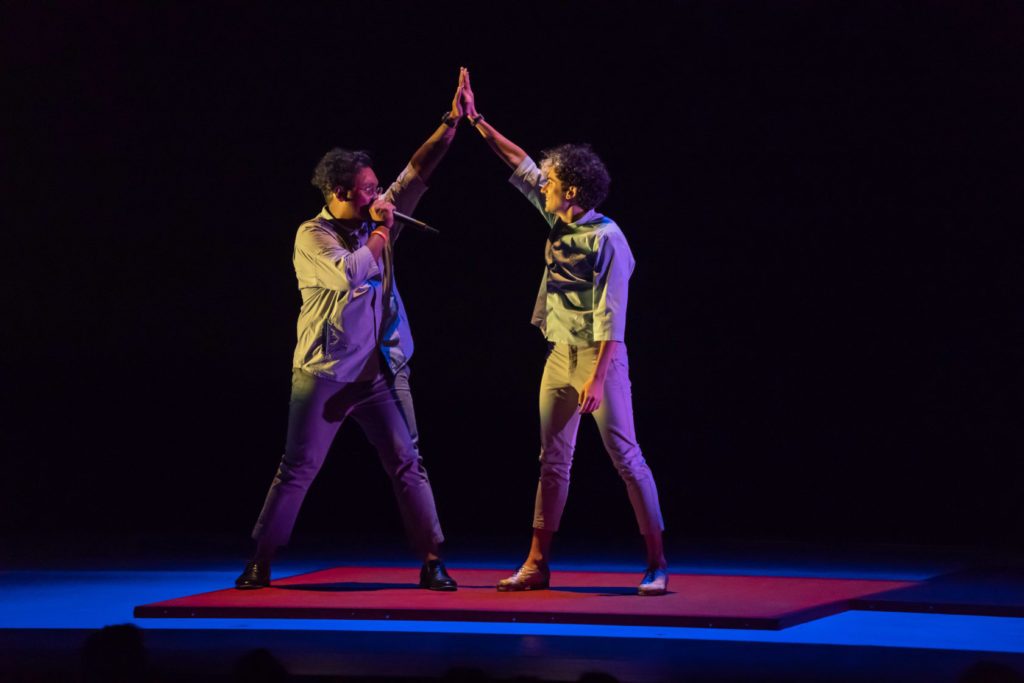

I also wanted to spend more time around Caleb Teicher & Company. Their exhilarating opening night closer, titled Bzzz, was crafted around witty banter between the tap dancing crew and beatboxer Chris Celiz. Before the curtain rose, Celiz slipped out from under it, mic in hand, seemingly dazed to find himself in front of a packed house of 2,000+. Realizing that we were probably expecting something from him, he dropped a few beats. Thumps issued from behind the curtain – which further befuddled Celiz. This back-and-forth went on until he figured out that someone behind the curtain probably wanted to have a word. The curtain rose and the dialogue escalated, sometimes pitting Celiz against the group, sometimes against just one dancer. Sometimes Celiz ended up arguing, rhythmically, with himself; at one point he wrapped up a delightfully nutty sequence with a whispered aside: “there are people watching you.”

Chris Celiz and Caleb Teicher in Caleb Teicher’s BZZZ (New York City Center Commission | World Premiere)

(Photo: Stephanie Berger)

It was clever, often hilarious, and stunning in the way beatboxer and dancers handed off rhythms, wove them together, and tossed in the occasional diversionary beat. Teicher’s crew are a diverse bunch, with their own distinctive dispositions, Teicher probably the most mischievous and carefree, the others slightly more earnest or wound a bit more tightly. Jabu Graybeal’s intensity and daring in particular counterpointed Teicher’s loose-hipped swagger. They all seemed infected with Teicher’s childlike glee at subverting social dance moves and finding new ways to make noise – sometimes just the barest drag of a flat foot on a wooden platform.

Sound levels hit the only sour note. The dancers’ footwork was well-served by City Center’s acoustics but Celiz was over-miked. We lost the crispness of some of his vocal acrobatics and the clarity of his husky basslines.

Sound levels proved a more serious affliction in Program 2’s closer, the Argentinian all-male troupe Malevo in a world premiere titled Salvaje (Wild). Between the 13 dancers and six musicians, there must have been 30 drums of various species hauled onstage and beaten to death at various points, not to mention the dozen or so boleadoras – lasso-like weapons with weights, deployed in this dance like jump ropes that cracked every time they hit the floor. The performers charged on and off stage in leather and chains for a novelty act long on testosterone and short on invention, that could’ve come straight off a Vegas stage.

Malevo (Argentina) in SALVAJE (Photo: Fabian Uset)

Malevo traffics in the malambo, a dance from Argentine gaucho traditions. In its present incarnation, it features insanely fast footwork and more articulation of the leg from the hip than flamenco, tap or Irish dance. The men performed this mostly in boots but went barefoot for the most intriguing episode, in which they sustained their furious speeds. Their virtuosic technique was partly dampened by the monotony of the choreography and the persistent jackhammering.

Program 2 was further undermined by a rambling contemporary ballet by Dana Genshaft for Washington Ballet, titled Shadow Lands. The ten dancers – a handsome and distinctly individual crew, attractively draped by Bartelme and Jung in glossy metallic hues and fancifully lit by Joseph R. Walls – dashed about frantically, looking very much hemmed in by the size of the stage. It’s not tiny. But since this piece seemed to demand more real estate, the company could’ve brought a work better suited to the space.

Puzzling program notes declared the intent of the choreography “to show that when broken pieces come together, the whole is better and stronger than when it is apart.” Nothing appeared broken except possibly the score by Mason Bates, seemingly cobbled from bits of muzak, jazz, symphonic film music and hissing electronica. To this, the dancers produced myriad ear-grazing extensions, springy jumps, off-kilter lifts, and modern twists on pirouette; in the general tumult, the men in particular managed to show off their classical chops and clean lines.

Washington Ballet in Dana Genshaft’s SHADOW LANDS (Photo courtesy New York City Center Fall for Dance)

I recall a quirky and conceptually tighter work by Genshaft in 2016 for the fledgling SFDanceworks, inspired by the life of George Sand. Granted, that was a solo, but it had an intriguing premise – unlike this kitchen-sink ballet.

From a fraction of the dance vocabulary employed in Shadow Lands, Mark Morris spun the intoxicating trilogy of Mozart Dances, of which an excerpt, titled Eleven, graced FFD’s Program 2. To the MMDG Music Ensemble’s spirited account of the Piano Concerto No. 11, the dancers, clad by Martin Pakledinaz in chic but practical lingerie, gamboled and negotiated fleeting alliances.

Members of Mark Morris Dance Group in Mark Morris’ MOZART DANCES (Photo: Robbie Jack)

Expansive, windswept movements in the opening section gave way to sterner, choppier action in which the arms made emphatic, almost war-like declarations. Yet conflict never arose in this dream world, populated by unflappable nymphs, who spoke in a sign language of enigmatic gestures: arms folded behind the head like moth wings, or flattened in profile as in Egyptian art; both hands gently cradling one cheek as if to suggest toothache; bodies zooming at an angle with arms outstretched, like planes coming in for landing. Flight patterns magically dissolved into moments of stillness, and the occasional brief nap. The dancers made more dramatic moves, like falling backward with no support, look as effortless as breathing.

The central unresolved mystery surrounded the sprightly, self-possessed Lauren Grant, who danced mainly at the fringes of the group – possibly an exile, or an authority figure who called the shots remotely.

Another female figure seemed to wield a mysterious influence over events that unspooled in the highly charged Dans l’Engrenage (In the Gear) from the young French company Dyptik. Fusing elements of voguing, popping, roboting, modern dance, and the traditional Arab line dance known as dabke, company artistic directors, Mehdi Meghari and Souhail Marchiche, have produced a scorching portrayal of power politics. In it, characters in business casual attire gathered around a meeting table as the frenzied gesticulations of one woman betrayed an obsession with power. She retreated to a downstage corner once her colleagues jockeyed for primacy, channeling their energies in a superb build-up of tension that commenced with the delicate but insistent drumming of fingers on the table. From a distance, the mysterious woman continued to haunt the proceedings.

Members of Dyptik (France) in Mehdi Meghari and Souhail Marchiche’s DANS L’ENGRENAGE (Photo: Ameen Saeb)

The office meeting from hell cast inescapable allusions to Kurt Jooss’ The Green Table from the 1930s, with its grotesque depiction of corruption and militarism. But once the table was whisked offstage, l’Engrenage pivoted toward anarchy as individual dancers fought for dominion over tiny fragments of territory, strikingly illuminated by Richard Gratas. This was the occasion for solo exhibitions of virtuosity that conveyed fear, envy, loneliness, a sense of being trapped. Unable to free themselves from some invisible labyrinth of greed, the ensemble turned on us, the audience. They didn’t actually charge us but it seemed like they might, for we were all complicit, weren’t we? There was a disquieting, almost terrifying element to the energy on stage. The dancers were riveting to watch, and the beguiling soundscape by Patrick de Oliveira skillfully wove Middle Eastern influences and inexorable contemporary beats.

We’re not even halfway done Falling for Dance this season (with three more programs in the line-up) and grateful for this rare chance to get to know companies that most New Yorkers would otherwise never get to see – at least not in the grandeur of City Center, and not for the unbeatable ticket price of $15.

– Carla Escoda reviewed Fall for Dance Programs 1 and 2 on Oct. 1 and 3, 2019 at New York’s City Center. –