Legendary ballerina Alicia Alonso, who helmed the Cuban National Ballet for 71 years, has died at age 98. Alonso was a star of American Ballet Theater and the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. She was also the first Western dancer to appear as a guest artist in the Soviet Union, at the height of the Cold War.

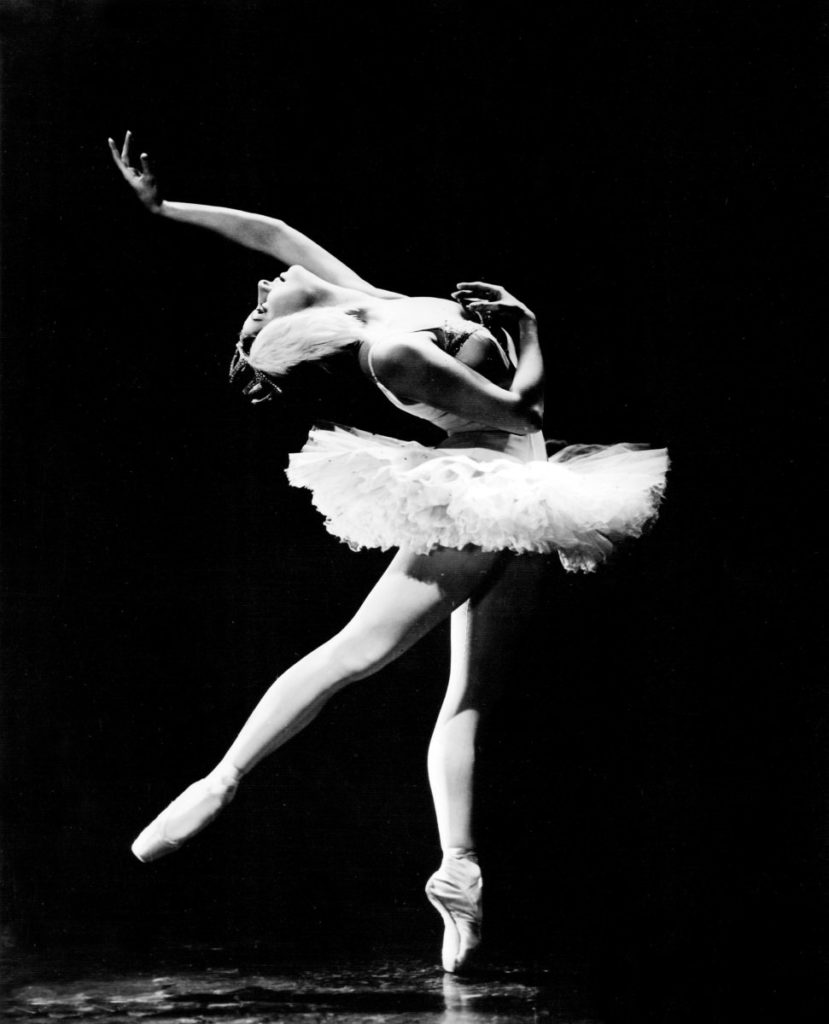

Alicia Alonso in SWAN LAKE, 1945 (Photo: Maurice Seymour)

Toba Singer, who wrote this obituary of Alonso, described meeting her in Havana:

A steady, no-nonsense gaze met mine. I asked the sturdy, bespectacled woman who stood behind a desk in an archway a few yards from the gated entrance to the National Ballet whether I might make an appointment to meet Mme Alicia Alonso.She looked back wordlessly. I placed a small white shopping bag on the reception desk. It contained my book, First Position: A Century of Ballet Artists. “This is for Mme Alonso,” I said, as I opened the book to a chapter headed “Alicia Alonso.” Then I retrieved another parcel from the bag, “And please give her this,” handing over a copy of my friend Frank Boehm’s film Alicia, a work in progress, which he and several dancers from Chicago had begun shooting some twenty years earlier. I asked the woman her name. “Fara,” she said. She waved her hand in the direction of a dancer I had noticed in Frank’s film. Now, twenty years older, he was walking quickly to escape a swirl of white dust as he lumbered under the burden of the two bags of cement he was carrying to the courtyard beyond. Fara then smiled slightly and explained that the dust from the renovation under way made the office uncomfortable for Alicia. She had the flu and was staying away most days. Fara promised to give Alicia my message, along with the items I had left, and to contact me at my hotel. When? Soon.

Two days later, on my way to an appointment across Villalon Park, I noticed Fara Rodríguez standing at the front gate of the ballet building. We greeted each other, and I reminded her of her promise to contact me. She smiled slowly and nodded. Alicia was still away from the office, but there was no need for concern. An answer would come—soon.

Later that evening I attended a performance of Giselle. The Cuban National Ballet’s version is its signature work. Its title role had brought Alicia Alonso the initial acclaim that launched her career when she stepped in for an ailing Alicia Markova in a New York Ballet Theatre performance more than seven decades earlier. As I mounted the stairs to the Antonio Mella Theater’s second tier, Fara, in a bright blue print dress, stepped out of the crowd. “She will see you in her office tomorrow at noon,” she said with an encouraging smile that nearly ended with a wink.

The following day, I downed the solo shot of Cuban coffee that Fara had offered me and then entered the inner office of the artistic director of the Cuban National Ballet. Alicia Alonso stood perpendicular to her desk with her right hand extended. She is blind, and so could not see me. The proffered hand signaled that the visitor should move toward her to make her presence known, to spare Alicia from calling out a greeting into an invisible void. I had known that she was blind, but I wasn’t prepared for a protocol that at once acknowledged and dismissed that blindness, a disability to which she has never given quarter unless forced.

Alicia thanked me enthusiastically for my book and the video, and we spoke of friends of hers whose lives and careers I had traced in the book, and of Frank Boehm’s film, and Frank himself. We chatted about Cuban dancers whom we both knew, and when I related a story about a defector’s characterization of life in the company, Alicia instantly converted the tale into a clever off-color joke. We laughed as if we were a couple of school chums, each shriek a delicious reproach to the defector’s caricature of Cuba. The shared humor made it less uncomfortable to reveal the purpose of my visit to my new friend.

“Alicia, I am here to write a book about Fernando.”

Few people mention Fernando’s name in Alicia’s presence, but I had no alternative. I would need her professional cooperation, even if she felt she could not endorse my project personally. I looked in her direction to gauge her reaction. She lowered her head and directed the eyes she shielded with sunglasses toward her folded hands. “Fernando? I see,” she said in a voice that was suddenly quiet, if a little deeper and more tremulous, and then there was nothing more. Apparently, no one had told her the purpose of my visit. I realized that I would have to wait a long time before raising any questions about Fernando with her, but how long? I would be in Cuba for just one more week.

That evening I saw the second cast dance Giselle. Again, as I entered the theater, Fara stopped me to say that Alicia had invited me to join her in the mezzanine lobby at intermission. As I made my way there, Alicia arrived on the arm of her current husband, Pedro Simón, a professor of philosophy and dance critic, who is the company’s co-executive director. Alicia made introductions, and the three of us spoke about the evening’s performance. During a break in the conversation, a man sat down alongside me and introduced himself as a critic for a U.S. Spanish-language dance journal. Indicating a young man who chatted with Alicia and then seemed to spring away and back again, the critic whispered, “That’s Fidel’s youngest son,” joking that “he has his father’s energy!” I nodded, but I was not in Cuba to engage in celebrity gossip. Over time, I came to find the young man’s interest in ballet more compelling than his provenance. During my visits to the island I would see him at other ballet functions, and was impressed that so young and well-known a male ballet devotee would show up alone, with no sheltering entourage running interference for him.

The scent of fresh-cut flowers greeted me when I opened the door to my room at the Hotel Presidente that evening. Switching on the light, I saw an enormous bouquet of two dozen red, white, peach, pink, and yellow roses in a vase on the desk next to my bed. Tucked into the bouquet was Alicia’s card, bearing a black slash meant to represent an “A.” I was overcome by simultaneous feelings of gratitude and embarrassment at having been received and welcomed so regally by a ballet legend I had admired for as long as I could remember. The bouquet’s perfume triggered the memory of a scene from my Bronx childhood. My devoted but frugal mother, having been instructed by my ballet teacher to provide me with a bouquet for the curtain call of my first recital, took scissors in hand and scaled the chain-link fence that separated our apartment house from the one behind it. A scrawny rose bush sat between the two buildings. She snipped several yellow tea roses from the lone bush, clambered back over the fence, and tied the pilfered flowers up in a half-inch-wide powder blue velvet ribbon, decommissioned from the contents of her sewing box. The other girls in The Skaters Waltz received store-bought bouquets, but as we dropped into réverence during our curtain call, that nosegay of yellow roses tied in velvet ribbon imparted the sense memory of the the guilty pleasure my mother took in risking life, limb, and reputation for a go at petty thievery to honor her six-year-old’s scant achievement. That long-forgotten, now reawakened moment resonated perfectly with what I appreciated about Cuban inventiveness: I happened to know that Alicia’s mother had once cut and sewn a Dying Swan costume for her daughter from a swath of white nylon appropriated from the wide hem of a pair of hotel curtains. I reflected on the sequence and significance of the day’s events and wondered when the right moment would arrive to ask Alicia to comment on Fernando’s contribution to ballet training in Cuba.

Sixteen months passed before I felt satisfied that I had done sufficient work with Fernando and his students, colleagues, and collaborators to write to Alicia to request that she answer questions about a man whose change of heart had broken hers. From the research I had done for my first book, I knew that there would have been no world-class ballet company in Cuba without Alicia’s outstanding achievements and the support of the Cuban people and their revolutionary government. My primary interest in Fernando issued from his life’s work as a pedagogue. If excellent teachers prepare dance students, and pull their best work from them, those same students inspire their teachers to refine their methods and approaches in an unending effort to discover their own best pedagogy. The distinction that places a teacher in a special category is that he or she educates not one dancer, but thousands, and teaches not one future teacher, but teachers of teachers for years to come. That is why a school of ballet, be it Danish, Russian, Italian, or French, is often identified with one singular teacher’s name. A current of enthusiasm ripples through the generations of dancers and teachers who offered heartfelt praise and gratitude for Fernando’s contribution of a scientific system that trained and prepared them for the ballet stage. One of them had urged me to write a book about him. Fernando’s younger brother, Alberto, had also made an immense contribution to the development of ballet in Cuba, with an innovative body of choreography that has been appreciated and reprised abroad. I had no plan to write a book on Fernando that would diminish or detract from Alicia’s or Alberto’s contributions, yet I continued to encounter a small number of individuals who insisted upon interpreting my project as an attempt to elevate Fernando’s role above that of Alicia or Alberto, if not the Cuban Revolution itself. I had no interest in taking sides in Alicia and Fernando’s divorce, nor in second-guessing the resulting proposal that Fernando move from Havana to Camagüey when it became clear that the couple’s artistic and personal differences were impeding the day-to-day work of the company and academy. Obviously, that decision removed Fernando Alonso irrevocably from the central leadership of the company, and such a change would not have been an option in Alicia’s case. Still, it carried with it the advantage of making it possible for him to not only play a pivotal role in strengthening Camagüey’s ballet company and school but also refreshing the ranks of the Cuban National Ballet with newly formed dancers from Camagüey.

Soon after I sent my note to Alicia, I received a reply from Pedro Simón, saying that Alicia would answer my questions if I were to submit them quickly, before the company left on an extended tour of Europe.

Excerpted from Fernando Alonso: The Father of Cuban Ballet by Toba Singer. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2013. Reprinted with permission.

Alicia Alonso and Toba Singer, April 2008 (Photo: Fara Rodriguez)

This is a moving story.

From Octavio Roca’s history of the Cuban ballet, I understand the relationship between Alicia and Fernando was stormy.

I would like to know if you believe that the Cuban ballet was restrained from moving forward with modern times because Alicia held on to power for so long. Or maybe the school and the company could not have survived without her, because Castro took a personal interest in her and her work.

Thank you.

Alicia and Fernando married very young. She was 14, he was 19. Alicia gave birth to her daughter Laura at 14. While their grasp of ballet was quite sophisticated and their dedication to their teenage dream to build a school and company in Cuba, unshakable, the marriage itself did not have time to “ripen” before immense pressures were inflicted by the Batista regime that resulted in them taking a principled stand at the cost of losing government funding. Added to this was Alicia’s encroaching blindness, which was a very personal, lonely struggle for her. Each of the two had a degree of expansiveness which served them and their undertakings in its own way, but it was not transferable between them.

The advantage of Alicia’s orthodoxy was that the Cuban National Ballet may well have been the last outpost of classical style under her artistic direction. While she welcomed guest choreographers and companies representing other styles to share works at the biennial international dance festival the BNC hosted, commissions from them for her dancers cost too much, shipping sets was unaffordable, or aspects of the U.S.-imposed embargo made it impossible to recreate the works as they deserved to be presented.

To me, the fourth partner in the bringing to life of the Cuban National Ballet was the socialist revolution in Cuba, which gave its whole-hearted support to the ballet. Compared to the finest ballet training available in the advanced capitalist nations, let alone the neo-colonial and semi-colonial countries, Cuba shines bright. An entire spectrum of dance has emerged in Cuba despite the limitations mentioned above. No one individual could stop or discourage it, even if they wanted to. As Fernando was fond of saying about many of the obstacles the Cubans have faced, “With one finger you cannot block the sun.”

Very interesting. Thank you.

Russian and Cuban ballet dancers who wanted better opportunities outside their countries used to have to make the dangerous decision to defect. But since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russians can travel quite freely. Their dancers don’t need to defect. However the Cubans are still stuck with that terrible choice. Both Russia and the U.S. bear some responsibility for the decades of stagnation in Cuba. Yet to my (non-scholarly) mind it seems that Castro’s regime punished generations of Cubans and Cuban dancers as much as, if not more than, it nurtured their finest institutions like Alicia Alonso’s Cuban National Ballet.