Exhibition reviewed by Leigh Donlan on 25 April 2024

Many American women artists escaped to Paris during the early 20th century where they found freedom from the gender, class, race, religious and sexual orientation limitations of home. Over sixty of these women are celebrated in the skillfully curated Brilliant Exiles exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Why these women left America was both personal and political. Their portraits and accompanying biographies ask viewers to consider why women feel compelled to leave their countries, or their personal situations, and whether America has since become a more tolerable environment for women artists.

“We talk about the lost generation. Many of these women were found in Paris,” clarified Robyn Asleson, curator of Prints and Drawings at the National Portrait Gallery during the April 25th press preview.

On the entrance walls hang three grand painted murals of Edward Jean Steichen’s original installation In Exaltation of Flowers, each over 10 feet in height. Steichen drew inspiration from Symbolist poet and playwright Maurice Maeterlinck’s book The Intelligence of Flowers (1907), each of the three women personifying a flower. Painter Katharine Rhoades is depicted as Rose-Geranium, along with Agnes Ernst Meyer and Marion Beckett as Petunia-Caladium and Golden-Banded Lily. The murals are reminiscent of Alphonse Mucha’s Art Nouveau style and flower series, though considerably more dazzling in gold leaf and tempura. These women were leading feminists, journalists, poets, painters, philanthropists and activists and part of Steichen’s Parisian social circle, among which he referred to them as “the Three Graces.”

Isadora Duncan has her own enclave of portraits. Rightfully so, as her ambition was not only to liberate herself from traditionally constrictive dance pedagogy, but to emancipate the female body from restrictive norms of sexuality and reproduction. Of her portraits, another Steichen oil painting, Moonlight Dance-Voulangis, is most alluring. Nature dominates the scene, as nature was Duncan’s steady inspiration for her movement and spirituality. Layers of electric turquoise and mauve suggest a partially clouded, moonlit sky under which a distant figure dances before an enormous tree in a garden. A shadowy group of spectators lounge in the forefront and gaze at the unclothed dancer, her movement captured like the ever-breathing tree, her slender arms waving her signature scarf overhead, like a wispy cloud. (It was a scarf that would later strangle her to death in a gruesome automobile accident.)

Writer, painter and dancer Zelda Fitzgerald’s Ballerina hangs nearby, a nod to her years of obsessive ballet training that eventually led to a nervous breakdown. The oil on canvas depicts androgynous bodies with bulging calf and thigh muscles. The figures are tossing aside decorative tutus, emphasizing the bodies’ singular importance.

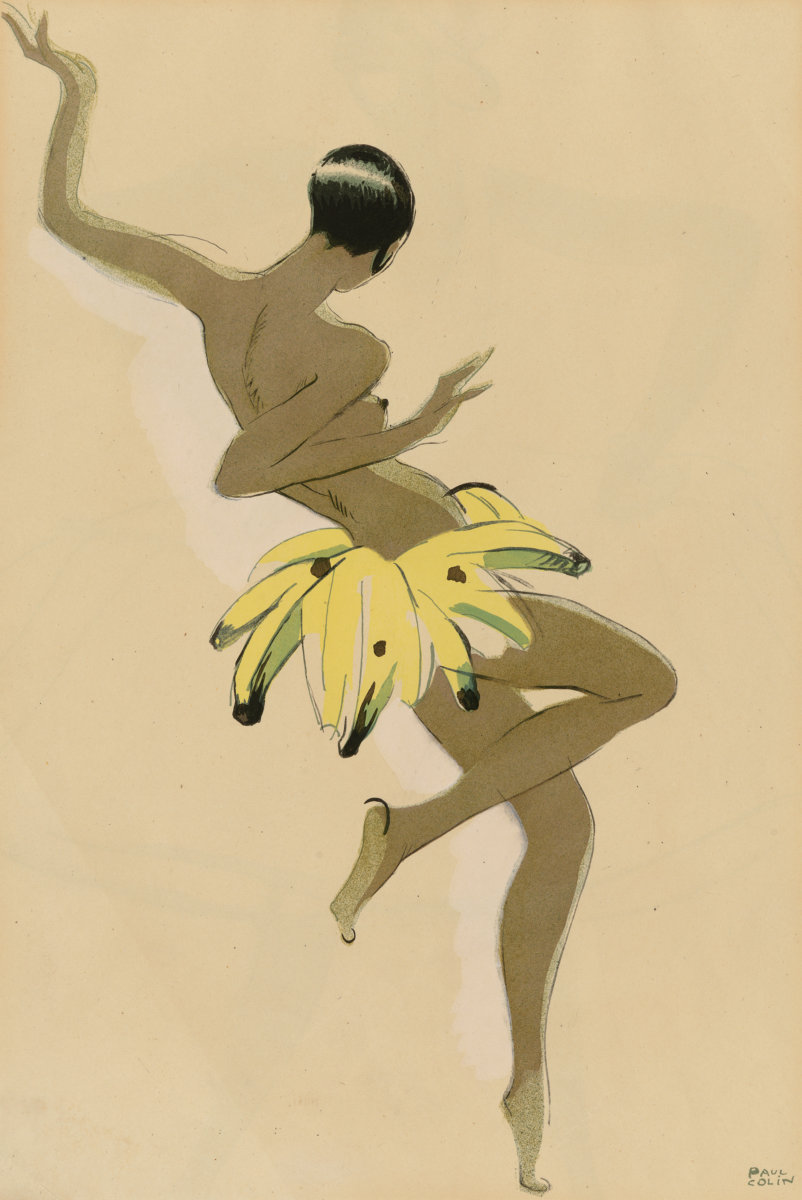

Josephine Baker est aux Folies-Bergère, a larger-than-life Michel Gyarmathy lithograph of a vibrantly costumed Baker, spans nearly 15 feet in height, framed in gold and bursting with red, orange and yellow hues like fireworks. The promotional 1936 poster was created by the costume and scenic designer for Baker’s En Super Folies at the Paris Folies Bergere and reflects the impact Baker had on both Paris and America. Baker took Paris by storm with her unique performance and costume styles, most notably her banana dress in Danse Sauvage. Baker was multitalented and was able to capitalize on the growing popularity of African and non-Western cultures in 1920’s France. During the German occupation of France, Baker – who had become a French citizen in 1937 – worked with the Red Cross and the Resistance, and as a member of the Free French forces. In America, she was renowned as a Civil Rights activist.

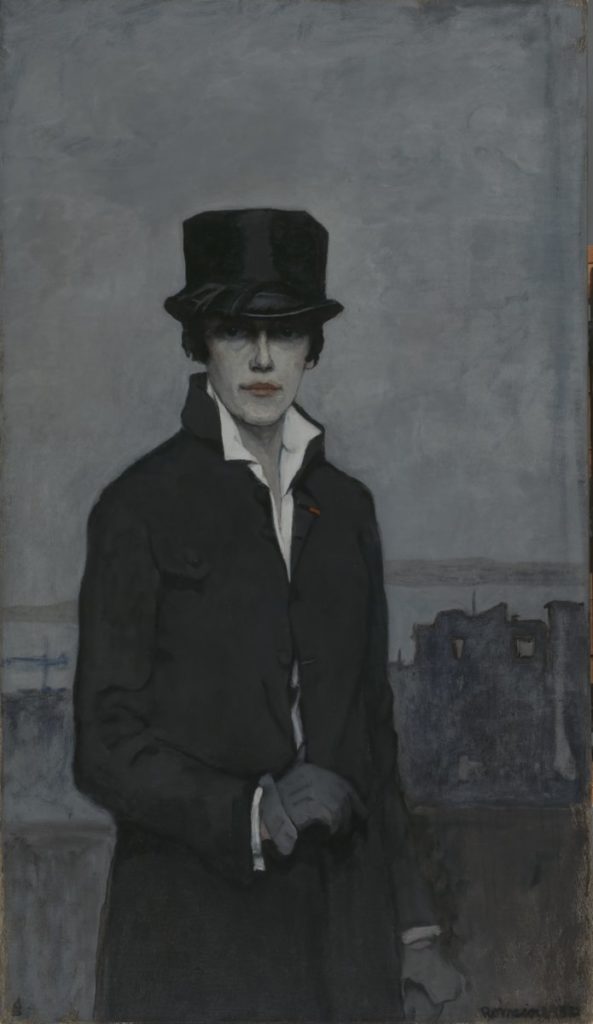

Other women represented themselves through self-portraiture, notably painter Romaine Brooks. Her oil on canvas exudes a silent command and a typically masculine presence, her gaze resolute but shadowed by a top hat, her dark clothing shapeless. Brooks spent her early years in Paris as a poor art student. She rejected the trends of Cubism and Fauvism and developed her own subtle yet powerful aesthetic, mostly portraiture of those closest to her, many of them women. During her studies, she was relentlessly stalked by a male fellow art student and ended up fleeing to Capri. She became increasingly disillusioned with Parisian high society, finding it ostentatious and distracting.

A regal Anaïs Nin by Natashia Troubetskoia (oil on canvas, 1932), sits on a throne draped in a heavy robe of rich velvet and fur; her doll-like face effuses innocence. The biography explains that Nin was intimidated by Paris’ competitive literary scene and that she felt the need to hide behind eccentric clothing. While writing her first book, she noted in her personal diary that she no longer needed clothing to express her uniqueness, stating “I have other things to do.”

An androgynous, heavyset Gertrude Stein by Pablo Picasso (oil on canvas, 1905-06), unapologetically fills the canvas in her legendary brown monk robe, appearing self-satisfied. Stein was one of the few women whom life-long misogynist Picasso respected.

Brilliant Exiles highlights how these women broadened the definition of modernism, how they catalyzed creativity and forged interconnected communities. Yet there were considerable gaps in these efforts. Entire communities of women artists would be excluded due to race and class. When Frida Kahlo arrived in Paris, she discovered that not all brown and black women would be as revered as Josephine Baker. Kahlo felt her exoticism was exploited by the French press who considered her work ‘craft’ rather than art. Some critics simply referred to her as ‘the artist’s wife,’ as she was married to Diego Rivera. And there were many women artists who simply didn’t have the means or connections to experience the novel freedoms that Paris represented for other women artists.

In today’s America, with significant rollbacks to women’s rights since the resurgence of the far right, there are new forces pushing women to seek spaces where they feel less threatened and more able to lead fulfilled lives. Those women who feel compelled to leave the country, or otherwise make new lives for themselves, may well find inspiration in this exhibition – as may women who decide to stay and fight the good fight.

Brilliant Exiles runs through winter 2025 at the National Portrait Gallery.