Leigh Donlan reviewed the matinee performance on Saturday, Nov 2, 2024, at Lincoln Center

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment is a tough novel to translate to the stage, let alone into ballet, but choreographer Helen Pickett, whose Crucible for Scottish Ballet and Emma Bovary for National Ballet of Canada generated much acclaim, has taken a fearless swing at the Russian epic for American Ballet Theatre.

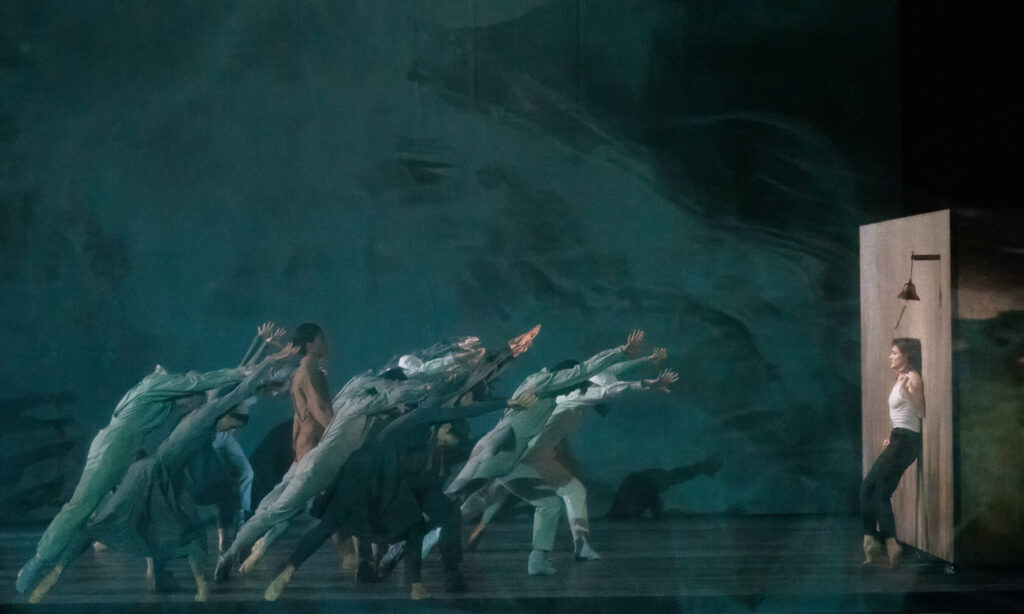

A monumental tale of psychological and moral chaos in a society damaged by extreme wealth inequality seems relevant to current world affairs but the connection is barely made in this production. What was billed as a world premiere (a risky thing to do in New York) turned out to be more like a first draft. There are certainly promising bones of a visionary piece. The strong narrative framework was there, and the highly gestural, poetic choreography in the opening scene for the ensemble was powerful: weighted movements, a rhythmic utilitarian mass, individuals gasping for air. If only the thematic convictions we saw here had been sustained throughout.

Drastic artistic liberties needed to be taken to translate a novel with so many inner dialogues and complex characters into dance. Presumably that’s what director James Bonas was enlisted to help with. Yet the lead characters often felt underdeveloped. They could have driven the story more convincingly, but certain artistic choices rendered important characters as stereotypical good guys and bad guys. It did not help that our attention was repeatedly drawn to a film projection that dredged up the murders committed by Raskolnikov in horror-film-like fashion with bright red blood splatters and close-ups of women screaming. Even less help were the projected surtitles, gratuitous and badly written. The danced narrative was pretty straightforward, but if you were lost at any point, the program synopsis was there to catch you up.

The ballet’s protagonist, Raskolnikov, is a destitute student who has just published a new theory – that the ideal man is above moral and ethical law because he is superior to the ordinary man. Saturday’s Raskolnikov was Cassandra Trenary, one of the company’s most versatile dancers, who alternated with Herman Cornejo and Breanne Granlund. This gender-neutral casting of the lead was risky but worked for me as it suggested that Raskolnikov’s experiences and moral dilemma transcend gender. It was a challenging role, on the level of Giselle, as Raskolnikov’s mental breakdown and spiritual crisis required chops, grit, technical versatility and intelligence, which Trenary has in spades.

The character of Sonya, danced by Sunmi Park, was painted as a saintly young woman driven to prostitution to support her family, her movement often reduced to pleading, heavenward gestures. Her consistently sorrowful face credibly symbolized what Dostoevsky described as “the suffering of all humanity;” it is she who ultimately convinces Raskolnikov to confess and seek redemption. Her character is integral to the story and, while we clearly saw that she was a woman of faith, the choreography and staging fell short in illustrating the depth and nuances of her character.

As Luzhin, the protagonist’s sister’s fiancé, Joseph Markey hilariously portrayed the grandly self-important villain, consistently calling attention to himself – preening, pricking and prancing in tightly tailored, peacock purple finery.

Calvin Royal III and Christine Shevchenko epitomized the strong and virtuous characters of Razumikhin and Dunya, Raskolnikov’s friend and sister, respectively. Royal made everyone feel safe, including the audience, and Shevchenko’s innate wisdom and grace brought calm to the escalating chaos. Royal opened his heart to Shevchenko with a deep cambré as their pas de deux unfolded – a dance of shared sorrow and mutual trust that represented hope, in one of the strongest scenes of the ballet.

Another redemptive character in the novel is Detective Porfiry, tasked not only with enforcing the law but also with getting Raskolnikov to abandon his theory of a superior race. The ballet’s Porfiry was more of a cartoon sheriff engaged in a cat and mouse chase. Thomas Forster did what he could with this characterization.

Melvin Lawoli as the Ever Watcher, a relatively minor character worthy of more attention, radiated the selfless suffering of a man who has dedicated his life to absolving others of their crimes, a Christ-like figure.

In contrast, the villain of the piece, the heinous Svidrigailov, is depicted more as a family-friendly bad guy than the violator of all social norms as painted by Dostoevsky. Patrick Frenette replaced James Whiteside on Saturday and played a convincing bully if not the psycho fearmonger of the novel. There’s nothing for his unconquerable will to will anymore after Dunya’s rejection, and he kills himself – an act sensitively depicted in shadows – just as Raskolnikov confesses his crimes, thus refusing to become the next Svidrigailov.

Patchy characterizations, particularly of Sonya and Porfiry, can be shored up. So, too, can failures of a more technical nature, such as the large plywood prop walls that constantly called disproportionate attention to themselves when maneuvered by the dancers between scenes. Was it really necessary for the dancers to double as stagehands? Other hiccups in scene changes due to mistimed lighting cues could be smoothed out with more tech run-throughs. And some unintentional comedy was provoked by the ineffective surtitles – like emphatically typed statements of the obvious: “THE DAM MUST BURST.” We know.

Excellent, a Pauline Kael-like review of the matinee performance!

I am a 30+ year ballet series subscriber at the Kennedy Center. Last night’s (2/15/2025) performance of Crime and Punishment was the first one, ever, that I left at intermission. The storyline was muddy, the music forgettable, video graphics laughable, and the dancing seemed to be an afterthought stuffed in between scene changes. Very disappointing.

I am curious: did they make any changes for the Kennedy Center performances? Because the New York premiere was, to put it politely, rough. But I thought it was exciting and brave. What a contrast to the previous world premieres of story ballets like Like Water for Chocolate and Of Love and Rage – so much money spent on designs for what turned out to be very conventional and not very imaginative choreographies. Crime and Punishment looked low-budget in comparison but not in a bad way, it had a sleek, brutal, powerful look to it.

What perfect timing for an epic Russian drama about corruption and salvation to come to the Kennedy Center, when a leader who was saved by God from assassination so that he could make America great again, who is taking his orders from a Russian mafia don, decides to invade the Kennedy Center.