Closing night of the 16th annual San Francisco International Hip Hop Dance Fest opened to the classic groove of The Police in a bleak, reflective mood – “when the world is running down, you make the best of what’s still around” – to which the five classy gentlemen of GroovMekanex in denim-blue button downs and white hats responded in crisp and witty style. The other local acts on this program did not fare quite so well, largely eclipsed by the imported talent.

Curated by legend-in-her-own-time Micaya, the festival takes hip-hop out of its customary competitive arena and on to the stage of the Palace of Fine Arts – which might sound like an incongruous setting for a gritty street art form, but the packed house on Sunday night hollered their appreciation as if we were all hanging out together on the corner of Mission and 24th at a sidewalk battle.

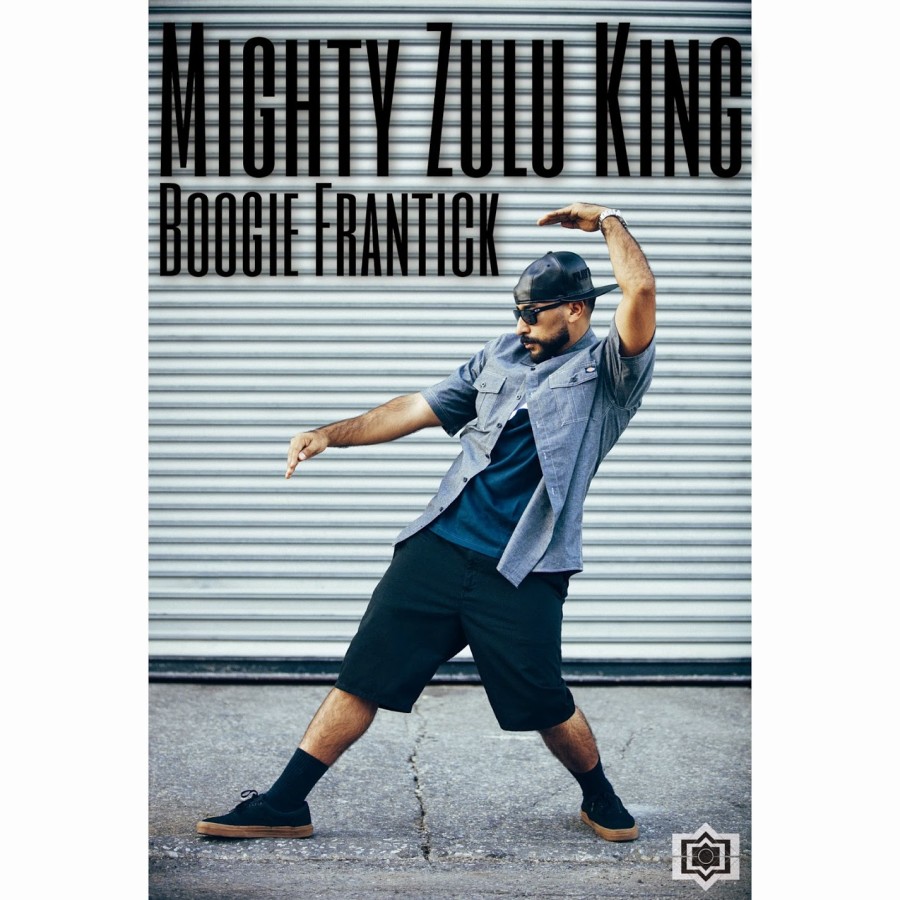

Ensemble performances were punctuated by two brilliant solo turns, both from Los Angeles: the first by the feisty Toogie-saurus (Teresa Toogie Barcelo) who channelled Nina Simone and the searing saxophone of the late great King Curtis in “I Put a Spell on You,” the second by the masterful Boogie Frantick to a hypnotic score by Flume and Chet Faker. Frantick’s silky moves – whether embodying ocean waves in silhouette against a backdrop lit sea-blue, or a graffiti artist using invisible walls and his own body as a canvas – and his dexterous stop-motion achieve a poetry that touches on tragedy as easily as it does the lighter side of romantic infatuation in No Diggity (“baby, you’re a perfect 10”).

Sacramento’s Greathouse of Dance (G.H.D.) boasted some impossibly young talent strutting their stuff like far more seasoned artists, with no narrative or props, and no costumes – apart from some formidable armor sported by the final quintet – just the moves straight out of the studio and off the street. They made it all look easy, with flashes of brilliance, never taking themselves too seriously.

Storytelling by the other ensembles proved a decidedly mixed bag. San Francisco’s Funkanometry tried to convey the angst of life in an asylum (both literal and figurative, according to program notes) but the young women in white, with painted faces that looked like the makeup artist from Twilight had a seizure halfway through the job, did not seem to have been given coherent persona to convey, and mostly came across as a bunch of hysterical teenagers emoting.

The four bewitching goddesses of Zamounda Crew, from Paris, went through a breakneck series of costume changes in their sly attempt to skewer the French obsession with haute couture, but were ultimately at their most powerful in street clothes.

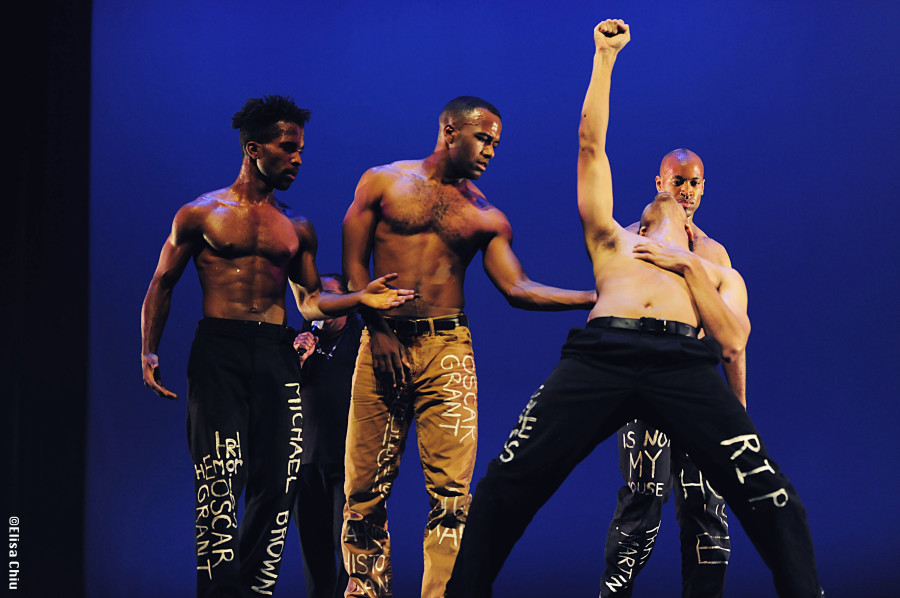

Despite the welcome presence of three singers onstage, and the rousing athleticism of five bare-chested dancers, Oakland’s Embodiment Project tribute to African American male victims of hate crimes and racial profiling fell somewhat flat. The names of Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin and Oscar Grant inscribed on the dancers’ jeans and the heartfelt rendition of Gregory Porter’s politically charged “1960 What?” about the 1967 Detroit riots made an obvious point, as did tired tropes like fists in the air, but the choreography meandered aimlessly.

In sharp contrast was the buildup of tension by the Brazilian Ritmos Family in their taut and mesmerizing “Fusion of Move.” Ritmos’ five male dancers integrate capoeira and contemporary dance moves seamlessly into the hip-hop vernacular to create images of desperation and hope. The result not only conveys attitude, but also hints at tormented backstories and a compelling narrative of transformation.

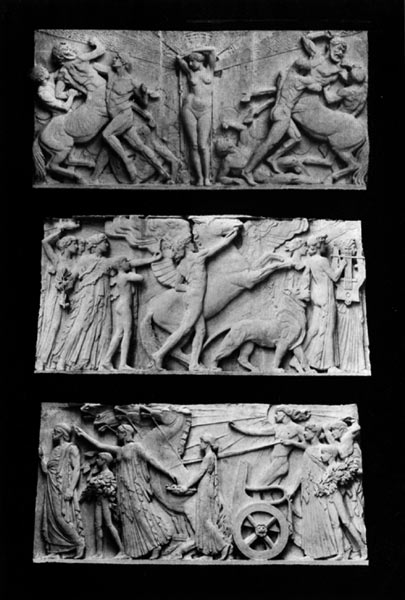

London’s BirdGang Dance Company told an equally striking tale in “Vice,” an Orwellian nightmare in which an office worker struggles to escape from his desk but finds himself glued to it in bizarre fashion. Once free, he is persecuted by hooded figures to the ominous buzz and throb of a score that melds electronic music with Tom Waits, horror film composer Christopher Young, and Radiohead. A lovely nymph (the luminous Kendra Horsburgh) hovers, in a spotlight, always out of reach. Lit cigarettes and cigarette smoke blown with admirable precision by the malignant spirits add a sense of menace to the intense, dramatic choreography. Remarkably, the entire piece echoes one of the three sculpted panels of the Grecian frieze that encircles the rotunda of the Palace of Fine Arts, entitled “The Struggle for the Beautiful”: Art, embodied by a beautiful nude woman, stands in the center while idealists struggle against the materialists, conceived as centaurs, who seek to crush Art.

Bruno Luis Zimm’s repeating stone panels around the entablature of the Rotunda at the Palace of Fine Arts, representing “The Struggle for the Beautiful”

BirdGang’s triumph did not entirely make up for the misbegotten spectacle of Mind Over Matter’s portrayal of an Amsterdam bordello. Choreographers today are marvelously adept at fusing all manner of dance styles with the hip-hop vernacular – why not burlesque? But this literal, ham-fisted exhibition of ladies in pleather, garters, sparkly bras and stiletto heels prancing about and servicing two hapless gentlemen under the watchful eye of a platinum blond-plaited, whip-wielding madam was conceived without a trace of irony, subverting the considerable power of hip-hop to convey righteous, youthful anger and rebellion.

This piece ranks with the insidious MTV evangelism, propagated by the likes of Beyoncé, Rihanna, Madonna et al who convince their fans that images of semi-clad women gyrating and fondling themselves on stage and on camera somehow empowers all women. (When in reality what empowers those performers and insulates them from exploitation are the enormous sums of money that buy them bodyguards, publicists, stylists, lawyers, tax accountants, private jets, and SUV’s with tinted windows.) That many in the audience roared at the overt depictions of ladies of the night performing oral sex on johns while in the splits, and then receiving oral gratification from the men while standing on their heads in the splits, merely suggests that they (audience) have not fully explored the array of adult channels offered by their local cable providers. Ballet to the People imagined the graceful statues of Weeping Women – another extraordinary ornament of the Palace of Fine Arts that stand guard at each corner of the Palace’s Corinthian columns – shedding copious tears on Sunday night at the leaden, unfunny female objectification.

If Mind Over Matter was shooting for satire or parody, towering examples can be found in the dance scenes in 1966’s Sweet Charity, choreographed and directed by Bob Fosse, the 1969 film of which the creators and the otherwise terrific performers of Mind Over Matter might do well to watch on Netflix.

Inevitable perhaps that an ambitious festival that unites troupes with such disparate backgrounds and manifestos will present unevenly. Hip-hop is indisputably the most potent dance form on the planet today, the most likely engine of artistic revolution, and while the battlefronts must be diverse, what Micaya and other guerrillas around the world are doing to infiltrate opera houses and concert halls is essential to winning the war.

– A version of this review appeared in the Huffington Post. –